From the November-December 2015 issue of News & Letters

by Ron Kelch

The shocking images of neo-fascist Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s Hungarian border guards brutalizing thousands of Syrian refugees—many asking why they were forsaken by the world in their fight for a multiethnic democracy when the Arab Spring spread to Syria—has put the global capitalist/statist system on trial. Refugees, asserting that it is not borders but their humanity that matters, reveal the hollowness of Europe’s claims it adheres to the most basic human rights and has regard for international law.

When 900 refugees perished off the coast of Libya in April due to Europe’s calculated neglect, Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi rightly called it our day’s Srebrenica. A Europe that prides itself on having learned better, must face the fact that fascism and ethnic cleansing didn’t disappear with World War II. The slaughter of over 8,000 men and boys at Srebrenica is etched in European consciousness as part of the reemergence of ethnic cleansing in Bosnia twenty years ago.

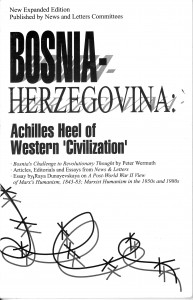

News and Letters Committee’s principled support of struggles for a multiethnic society then and now stands out from most of the Left. (See Bosnia-Herzegovina: Achilles Heel of Western Civilization, hereafter referred to as B-H.) “World in View” columnist Gerry Emmett recently revisited the discussion of Mihailo Marković. Marković (1923-2010) was part of a Marxist humanist movement in Yugoslavia in the 1960s and 1970s questioning prevailing Marxism. After the collapse of the Yugoslav state in the 1980s, he became central to the nationalist Serbian regime that, in the 1990s, committed war crimes, including mass rape, genocide and ethnic cleansing.

In “Our Right to Exist: Bosnia and the Marxist-Humanist Archives,”[1] Emmett raised the question: Though we criticized Marković’s transformation into opposite and strongly opposed him politically when he became an ideologue of national socialist, Serbian fascism, why have we never clarified our differences with his Marxist humanism? I further want to ask: Why didn’t we work out our specific differences over Marx’s 1844 Humanist Essays, upon which Marković’s Marxist humanism also relied?

MARKOVIĆ VS. DUNAYEVSKAYA

Emmett writes that while the need for a philosophic critique of Marković was discussed, none materialized. Sharply contrasting Marković with Raya Dunayevskaya on methodology, Emmett refers to her 1987 essay included in B-H, “A Post-World War II View of Marx’s Humanism, 1843-83; Marxist Humanism in the 1950s and 1980s,” which summarized Marx’s humanism for a Yugoslav audience. Emmett shows how such a critique can begin:

Marković: “Many followers of Marx have misinterpreted his method and construed it as a more or less closed methodology…But for Marx dialectic was primarily a weapon of social criticism, a means of explaining existing social reality that would immediately point the way to revolutionary action.” (Socialist Humanism, 1965)

RD [Dunayevskaya]: “The self-development of ideas cannot take second place to the self-bringing-forth of liberty, because both the movement from practice that is itself a form of theory, and the development of theory as philosophy, are more than just saying philosophy is action. There is surely one thing on which we should not try to improve on Marx—and that is trying to have a blueprint for the future.”

These quotations are rich in difference. Here I’ll just point to the philosophic difference between “immediacy” in Marković versus the development by RD of philosophic categories adequate to encompass spontaneity, different cultures and forms of development, and non-state forms of collectivity. Without this development Marković fell into the most hideous kind of blueprint making possible.

Emmett initiated a multi-faceted discussion on Dunayevskaya’s encompassing “philosophic categories” vis-a-vis Marković. My focus is to continue with the contrast between Marković’s view of Marx’s methodology as “immediate…revolutionary action” and methodology that insists “the self-development of ideas” doesn’t take a back seat to “the self-bringing forth of liberty.”

In his 1844 Humanist Essays Marx criticized views like Marković’s even as he intimates Dunayevskaya’s. The second view of methodology resonated strongly with Dunayevskaya’s chapter in The Power of Negativity: “Power of Abstraction” from which I got the form for my report to the Plenum on “Marx’s Self-determination of the Idea as Organization.”[2]

Contains: Raya Dunayevskaya’s “A Post-World War II View of Marx’s Humanism, 1843-83; Marxist Humanism in the 1950s and 1980s” as well as articles, editorials and essays from News & Letters. $10, includes shipping. To order click here.

THE SELF-BRINGING FORTH OF LIBERTY

Dunayevskaya’s 1987 essay looked to encompassing philosophic categories already in “Marx’s Humanist Essays” (B-H, 105). In Rosa Luxemburg, Women’s Liberation and Marx’s Philosophy of Revolution Dunayevskaya further pinpointed that the source, the precise moment of “self-clarification” and birth of the “self-determination of the Idea” of Marx’s Historical Materialism came early on in the Essays with the concept of “Alienated Labor” (125). Alienated labor, says Marx, has turned human life activity into a mere means to life. This violates humanity’s species essence or species being: self-determining, free, conscious activity that is not a mere means but the first necessity of life. Human species essence never “directly merges” with any particular stage.[3] Yet it is important to recognize that this idea of freedom is an unchanging universal that particularizes itself in ever new ways in the course of human development.

In other words, Marx’s concept of species being is open to all the new ways freedom particularizes itself through new human relations. From within each human being comes the need to be needed as a human being, that is, recognized as the architect of one’s life activity. Marx hones in on alienated labor confronting private property that makes “worker’s own life-activity” something sold and “only a mere means … to exist” (CW, 9:202). But from the start the woman/man relation is the most fundamental (CW, 3:295-6) in revealing whether a human being is needed as a human being. When Marx witnessed global capitalism’s colossal expansion of wealth through the slave trade—a new, especially brutal and specifically capitalistic form of racialized slavery—the self-activity of Blacks in the U.S. to reclaim their humanity as free, conscious agents of their life activity became the vanguard of the idea of freedom for a new international workers’ movement.

THE SELF-DEVELOPMENT OF IDEAS

Dunayevskaya associates Marx’s concept of human essence, which encompasses multiple aspects of the drive to be needed as a human being, with Hegel’s “self-bringing forth of liberty.” The “self-bringing forth of liberty” is a shorthand expression for Hegel’s appearance of philosophy “…as a subjective cognition, of which liberty is the aim, and which is itself the way to produce it” (Hegel’s Philosophy of Spirit, para. 476). In other words, the “self-bringing forth of liberty” would involve explicitly engaging new freedom movements with the universal of self-determining free, conscious activity as the first necessity of life. This universal did shape the whole of Marx’s life of revolutionary theory and practice, including a key principle to envision and realize freedom in a post-capitalist society. When Marx explicitly returns to this principle to guide a post-capitalist future in his 1875 Critique of the Gotha Program, projecting the principle is what sets a specifically Marxist organization apart from all other tendencies (CW, 24:87).

From the start (1844) the self-development of the idea of Marx’s Historical Materialism and the “self-bringing forth of liberty” were bound together. Marković and others are oblivious to how the idea of freedom itself, with which Marx begins, undergoes a dramatic self-development already in the 1844 Essays. In his contribution to Socialist Humanism,[4] Marković stops halfway with the “positive” in “the annulment of alienated existence,” citing Marx on communism or “practical humanism” through the “annulment of private property” and “atheism” as “theoretical humanism” (86). Marković certainly recognizes that Marx saw communism in terms of “negation of the negation” (CW, 3:306), criticizing Stalinism for rejecting this “key principle” (90).

Even though communism is the positive that comes out of the necessary negation of private property which exacerbates alienated labor, this “negation of the negation” is not enough. This “practical humanism,” too, has to be transcended for “self-deriving…positive humanism” to “come into being” (CW, 3:342). Communism as “the appropriation of the human essence through the intermediary of the negation of private property… [is] not yet the true, self-originating position but rather a position originating from private property…” (CW, 3:313). By itself communism is merely an “intermediary” either on the way to, or in the way of, the full realization of the “human essence” in reality.

Self-determining, free, conscious activity as the first necessity of life is the irreconcilable, absolute opposite to alienation and does not stop at any particular stage of development. Without explicitly recognizing just that, one is subject to becoming identical to what one opposes which, in the case of communism, is just another form of property, collective instead of private. What Marx simply noted, that it is “a real advance to have at the outset gained a consciousness of the limited character” of communism (CW, 3:313), demands to be brought front and center if humanity is going to avoid still another barbaric transformation-into-opposite like Marković’s.

Because Marx began from the absolute opposite of alienation, he addresses the crucial question of our day which has seen so many revolutions transform into their opposite: “what happens after revolution?” For Marković, Marx’s humanist “dialectic was primarily a weapon of social criticism, a means of explaining social reality that would immediately point the way to revolutionary action.” In that mode one likewise never gets fully beyond one’s opposition to social reality, never fully comprehends how human species being positively generates that social reality anew.

Specifically human development, “real species consciousness,” can only be realized when “negation of the negation” becomes a “self-referred negation” where each one experiences reality as the self-movement of the idea of freedom that is always open to the new (CW, 3:342). As our time confronts global capitalism’s multiple crises and absolute threats to humanity through a drift into fascism, terror, total war, or ecological apocalypse, no halfway dialectic will do. There is no substitute for re-creating Marx’s original philosophy of a new humanism.

[1] To see Gerry Emmett’s talk, send $5 to our Chicago address (includes postage) and order Post-Plenum Bulletin #1.

[2] Both reports are available in “Post-Plenum Bulletin #1” and mine is also available online at ronkelch.wordpress.com

[3] Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Collected Works (International Publishers: New York) vol. 3, p. 276, further referenced as “CW” with the volume number and page number in the text.

[4] Published in 1965, Socialist Humanism, an international symposium edited by Erich Fromm, is a classic reference to many Marxist humanist thinkers. Markovic’s contribution, “Humanism and Dialectic,” summarized his return to Marx’s early work. Raya Dunayevskaya’s contribution, “Marx’s Humanism Today,” is available at: http://rayadunayevskaya.org/ArchivePDFs/3565.pdf.

Ron Kelch’s philosophical dialogue (N&L, Nov-Dec 2015) has a particular import to the dilemma of unfreedom that has the whole of humanity so deeply ensnared. The reader is presented with a contemporary view of man’s inhumanity to man. Men lack the ability to be human when there is not a clear recognition that it is within the process of human social interactions that humans discover their true humanity. That is what Victor Orban’s Hungarian border guards displayed against Syrian refugees. Why do these kinds of human catastrophes continue to haunt humanity? What is a way forward that leaves human catastrophes in the dust bin of history? The writer believes an answer exists within the context of this philosophical dialogue.

It grew out of the necessity to clearly distinguish the fundamental difference between Mihailo Markovic’s Marxist Humanism and Raya Dunayevskaya’s Marxist-Humanism. To see the distinction, the reader is placed on the ground of Marx’s 1844 Humanist Essays. The difference centers on the concept of methodology. Markovic’s viewpoint is that it is a weapon of social criticism, a means of explaining existing social reality that immediately points to revolutionary action. Dunayevskaya’s development of philosophic categories encompasses spontaneity. Various cultures and their particular forms of development and non-state forms of collectivity. In a nutshell, it is a closed methodology vs. an open one.

Kelch focuses on the contrast between Markovic’s view of methodology as “immediate … revolutionary action,” and methodology that insists “the self-development of ideas” doesn’t take a back seat to “the self-bringing forth of liberty.” In the section titled “The Self-Bringing Forth Liberty” Kelch shows the nature of both “the self-development of the idea” and “the self-bringing forth of liberty.” Kelch reveals to the reader that Dunayevskaya’s 1987 essay looked to the philosophic categories already in Marx’s Humanist Essays. Dunayevskaya further pinpointed the source of philosophic categories in her book, Rosa Luxemburg, Women’s Liberation and Marx’s Philosophy of Revolution. That source lies within Humanist Essays, particularly “Alienated Labor.”

Both “self-development of ideas” and “self-bringing forth of liberty” are cognitive capacities of human beings. It speaks to the cognitive process of conscious development. There is no separation between those two within Marx’s philosophy. Why didn’t Markovic grasp this in his engagement with the Humanist Essays?

Dunayevskaya had a much more careful reading of the Humanist Essays. Kelch summarizes it, “it is important to recognize that the idea of freedom is an unchanging universal that particularizes (italics mine) itself in ever new ways in the course of human development.” Kelch gives a most telling example made by Marx himself … “the self-activity of Blacks in the U.S. to reclaim their humanity as free agents of their life activity became the vanguard of the idea of freedom for a new international workers’ movement.”

The last subsection, “The Self-Development of Ideas,” is where Markovic’s rift with Marx’s humanism is more explicit. The principle which explicitly sets a Marxist organization apart from all other tendencies is the universal, self-determining, free, conscious activity as the first necessity of life. Why? This universal shaped the whole of Marx’s life, of revolutionary theory and practice, including a key to envision and realize freedom in a post-capitalist society.

Markovic’s inability to grasp the real essence of Marx’s historical materialism left him with a narrow interpretation. As a result, Markovic concluded that Marx’s humanist “dialectic” was primarily a weapon of social criticism, i.e., a means of explaining social reality that would immediately point a way to revolutionary action. Kelch showed the negative result of Markovic’s interpretation: “In that mode one likewise never gets fully beyond one’s opposition to social reality, never fully comprehends how human species being positively generates that social reality anew.” In short, the prevalent present-day reality is that many Leftist tendencies are bereft of a revolutionary philosophy and at the same time speaks to the very reason why humanity has had to continuously witness the revolutionary process turned into its opposite: a barbaric counter-revolution.

The significance of Marx’s revolutionary philosophy is that it gives humanity a way forward. Kelch wrote, “Specifically human development, ‘real species consciousness,’ can only be realized when ‘negation of the negation’ becomes a ‘self-referred negation’ where each one experiences reality as the self-movement of the idea of freedom that is always open to the new.”

The profundity of this philosophic dialog is that it [contributes to] airing the humanist dialectic of Karl Marx’s Marxism so that an end comes to the continuously aborted revolutionary process.

For Freedom,

Faruq

12-1-2015

Mihailo Markovic became an accomplice, even to an extent an architect, of the 1990s genocide in Bosnia and the rest of what had been Yugoslavia. That is his real crime. The idea that there is a link between this degeneration of his thought and some inadequacy in his philosophy from the 1960s is interesting, but the philosophic dialogue “Behind Markovic’s turn to fascism was rift with Marx’s humanism” (Nov.-Dec. N&L) makes no argument to show such a connection. Degeneration of thought is not a unilinear phenomenon flowing inexorably from a philosophical error. Nor does the article make clear what “halfway dialectic” can be found in Markovic. Too much depends on reading the word “immediately” from one sentence as if it implies excluding mediation from Marx’s dialectic and limiting it to action. The criticized sentence clearly intends to contrast Marx’s dialectic as “activist and revolutionary” as against a reified, closed methodology. The second part of Kelch’s criticism is the claim that “Marković stops halfway with the ‘positive’ in ‘the annulment of alienated existence,’ citing Marx on communism or ‘practical humanism’ through the ‘annulment of private property’….This ‘practical humanism,’ too, has to be transcended for ‘self-deriving…positive humanism’ to ‘come into being.'” To say this means stopping halfway is a heavy burden to place on the fact that Markovic quoted a particular passage from Marx, and Kelch seems to disregard what is quoted earlier in the same paragraph, Marx’s praise for Hegel’s insight “into the appropriation of the objective being through the supersession of its alienation.” Kelch may be right that there is a halfway dialectic, but the piece does not articulate what it is or prove it. And what does any of this have to do with Markovic’s turn to genocide?

Ron Kelch’s essay does not purport to show a causal link between Markovic’s interpretation of Marx and his turn to a genocidal criminal. How is it a critique to assign a purpose that isn’t there and then state that the work did not meet that purpose?

In my reading of his essay Kelch showed how neither Markovic nor News and Letters Committees at the time measured up to the uniqueness of Dunayevskaya’s Marxist-Humanism, which would help us to not fall into the many traps that lay in wait, the pitfalls of a “dialectic” that does not go all the way to Absolute Negativity in the form of self-referred negation which is also a self-determination of Marx’s own humanism: free conscious activity as the first necessity of life. Re-articulating the importance of “free conscious activity as the first necessity of life” has stood out for me since we re-read the 1844 Essays in the Bay Area when new people were interested in finding out more about Marx.