From the January-February 2021 issue of News & Letters

Editor’s note: Originally titled “These Uncivilized United States: Murder of Rev. King, Vietnam War,” the editorial excerpted here was published in the May 1968 News & Letters. It speaks to King’s actual, non-sanitized life and legacy, as well as to the ingrained violence of U.S. racism, including what was seen on Jan. 6 at the U.S. Capitol. Footnotes were added by the editor.

by Raya Dunayevskaya

The long hot summer began in spring this year with so fast-moving a scenario that neither the startling abdication of LBJ nor his loaded “peace feelers” had time to sink in before the shot that killed Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. reverberated around the world. LBJ’s popularity, which had risen late Sunday night with his announcement of de-escalation of the Vietnam War, plummeted down with the news of King’s assassination on Thursday, April 4.

No serious commentator abroad thought this was an act of a single individual, insane or just filled with hatred. Everyone took a second look at this racist land where acts of conspiracy to commit murder “and get away with it” are spawned out of an atmosphere emanating from a White House conducting a barbaric war abroad, and a Congress which allows its “illustrious members” to sound like rednecks bent on murder when the “Negro Question” is the issue. Just the week before the assassination, those legislative halls were resounding to demands “to stop King” from leading a Poor People’s March into Washington. . . .

Though President Lyndon Johnson ordered the flag flown at half-mast and shed many a crocodile tear, one thing was clear: no overflow of staged tears by the administration could possibly whitewash the Presidency and these uncivilized United States of America. The murder of Rev. King pushed even the Vietnam War off the front pages of the papers as Black revolts struck out in no less than 125 cities. . . .

The very fabric of American civilization was unravelling so that its racism stood stark naked for all the world to see. When “law and order” was restored, nothing was in the same place, nor will it ever be. . . .

POVERTY VS. AFFLUENCE

Though all the “dignitaries” were duly represented at King’s funeral, the difference between the pomp and pageantry of the funeral of the assassinated president five years ago and the present mule-drawn carriage bearing the body of Dr. King was stark.

This was due not only to the difference between a president and a “civilian.” Nor was it just the difference between a rich man and a poor one; Rev. King wasn’t all that poor. He had chosen the mule-drawn carriage as symbol for his Poor People’s March on Washington not only to underline the difference between affluence and poverty in this richest of all lands, but mainly to stress the backwardness of the conditions of the Black farmer in this most technologically advanced land.

The Negro has always been the touchstone of American civilization, exposing the hollowness of its democracy, the racism not only at home but also in its imperialist adventures. And the latest of a long list of martyrs in the battle for freedom was too much flesh of the flesh of the whole of American “civilization” to be capable of cover-up by all the flags flown at half-mast. After the Black man had had his funeral, what then?

The true measure of both the grief and determination to go on with the civil war for freedom was seen, in one form, in the mass outpouring of 150,000 who were in Atlanta, and, in another form, in the Black revolts in the cities.

SELF-STYLED ‘REVOLUTIONARIES’

Enter the self-styled “revolutionaries” with their deprecation of the role of Dr. King in the Movement. It is the obverse side of the hypocritical mourning by the administration. Parroting the talk of the white power structure, they equate King’s life with his stand on non-violence. That isn’t why Rev. King was subjected to 30 jailings. It isn’t why he earned the most unbridled attack from Congress. And it isn’t why he was marked for assassination.

On April 8, when Rev. King’s body was still lying in state, one such self-styled “revolutionary”—William Epton—rose to speak to a campus meeting of some 200, mostly white CCNY students. Just because he was a Black man, he had the gall to speak as if he represented the Black community as he yelled “We don’t mourn King. . . . We saw King as an obstacle to the Black liberation movement.”

Outside of the inhumanity of such a statement about one man who was struck down at the age of 39, having given his whole adult life to the Movement, the misreading of the history of the Black liberation struggle is self-evident when one considers that Rev. King was murdered because he came down to Memphis to assist Black workers locked in class struggle with the white power structure.

But this isn’t a question only of the past, either that of one man or of the Movement. Rather, it is a question of perspective, of future development, and is not unrepresentative of some Black nationalists and their white followers in the so-called New Left. It becomes necessary therefore not only to set the record straight, but what is even more important, to see that the objective movement of history isn’t replaced by petty-bourgeois subjectivism—be it expressed in the open air crudely by a William Epton, or more subtly in a vanguardist church by Rev. Albert Cleage.[1] Any voluntarist approach cannot but have tragic consequences for the American revolution that is yet to develop.

VOICES FROM BELOW: 1956-66

In retrospect, the coincidence of Rev. King’s beginnings as a leader of the Montgomery Bus Boycott with the totally new stage of Negro revolt appears, not as accidental, but the right person at the right place at the right time. That is to say, it bespeaks the objective significance of Rev. King’s role in that struggle, sparked by the refusal of a Negro seamstress, Rosa Parks, to give up her seat in the bus to a white male.[2]

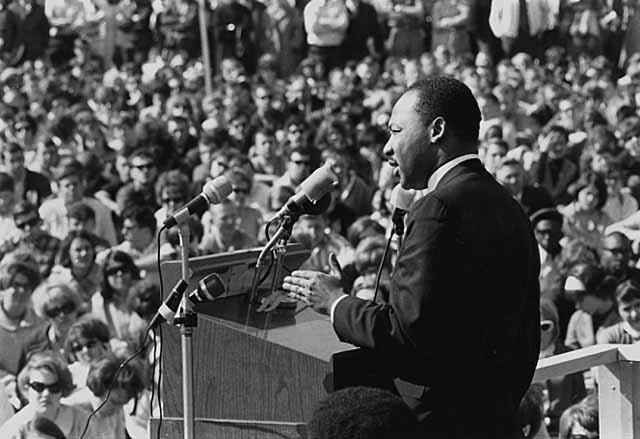

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. speaks against the Vietnam War at University of Minnesota in St. Paul, April 27, 1967. Photo: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Martin_Luther_King_Jr_St_Paul_Campus_U_MN.jpg

We didn’t need the lapse of a decade before we sensed the historic significance of “the forceful voice of the Alabama Negroes who have taken matters of freedom into their own hands.” At the very moment of its happening, we compared the significance of these actions against the white power structure in Alabama to the Hungarian Revolution against Russian Communism, stressing that “the greatest thing of all in this Montgomery, Alabama, spontaneous organization was its own working existence.”[3]

But let us add here that it wasn’t only that Rev. King was there. It is that he knew how to listen to the voices from below and, therefore, to represent them in a boycott that lasted 382 long days during which it was in mass assembly some three times a week, daily organized its own transport, moving from a struggle against segregated buses to a demand for hiring Negro bus drivers—and won on both counts.

If there were those who hadn’t recognized this totally new stage of Negro Revolt in 1956, none failed to see, on the one hand, the barbarism of Bull Connor’s police dogs, water hoses, electric cattle prods, and, on the other hand, the bravery, daring, and massive persistence of the Negroes in Birmingham in 1963.

Again King was there. This time he tried also to give philosophic expression to the struggle against segregation. In his famous letter from a Birmingham jail to the white clergymen who objected to “illegal acts,” Rev. King wrote: “We can never forget that everything that Hitler did in Germany was ‘legal’ and everything the Hungarian Freedom Fighters did in Hungary was ‘illegal’ . . . To use the words of Martin Buber, the great Jewish philosopher, segregation substitutes an ‘I-it’ relationship for the ‘I-thou’ relationship and ends up relegating persons to the status of things.”[4]

Both nationally and internationally, both in relationship to the non-violent tactics here and the more violent phases of the African revolutions, Dr. King had developed to the point where he let nothing stand in the way of the struggle for freedom.

Though the humanist philosophy he then unfolded was quoted from Martin Buber, and not Karl Marx, he was not unaware that the African Revolutions based themselves on the Humanism of Marx.

ISOLATION

It is true that, by 1965, Rev. King faltered seriously as he was completely baffled by the newer stage of Negro revolt in Harlem and Watts and all the other long, hot summers, marked by the shouts of “Burn, baby, burn!”[5] But the isolation from the Negro masses at that moment was not due solely to his belief in nonviolence.

Those leaders who made a principle of the need for violence for self-protection were just as far removed from the actual Black revolt in the Northern cities as were those like King who persisted in preaching nonviolence.

For something a great deal more significant than violence vs. non-violence was involved in the new Black mass revolt. New perspectives were needed. A new comprehensive view; new allies among rank-and-file labor and other white militants to help in the arduous task of tearing the whole exploitative society up by its roots.

New leaders did arise, but they traveled everywhere from Cuba to Algiers. They were not where mass power lay—on the streets. They were not working out a new relationship of theory to practice on the basis of it and hence could not give expression to the new in the masses.

1967-68: THE VIETNAM WAR & DEATH AT HOME

The sickness unto death with the Vietnam War on the part of the youth, both white and Black, at first got but little response from Rev. King. However, there was no doubt that the dream he had of achieving equality for Negroes had turned into a nightmare as he moved North and came up against the mightier white power structure there in the person of Chicago city boss, Mayor Daley.

At the same time, the white youth that had gone South to help in the civil rights struggles had clearly, since 1965, shifted to creating an anti-war movement to oppose the barbaric imperialist war.

Many a tactic of the earlier fight—sit-ins as well as teach-ins, marches as well as days of protest on an international scale—had been applied by them to the present struggle, which they saw as critical both to their lives and to any movement “to end poverty.” With $20 billion being poured annually into the Vietnam War, the administration’s “Great Society” was the forgotten Black waif left both homeless and starving in the backwaters of the South as well as the ghettoes of the North.

Clearly, without a new unifying philosophy of liberation that would relate itself to the new reality, it was impossible to move forward. The new voices of revolt in the North as well as Virginia and Mississippi that had not been heard in 1965 were finally heard to say “Hell no, we won’t go!” in 1967.

UNITING MOVEMENTS

Dr. King came out against the war and tried uniting the two movements fighting the administration. At once, he became the target of the most slanderous campaign which showed also its arrogance in telling him to keep hands off other than “Negro problems.” In this, the administration was joined by the leaders of the NAACP and Urban League. Gone was any pretense to Black unity. Gone was “approval” of King as a man of nonviolence. The deep-freeze against “the war on poverty” was no longer restricted to Southern bourbons but was the dominating line of the Presidency.

It is this atmosphere of capitalistic monolithism that Rev. King confronted as he planned what became his last and greatest battle: to combine the poor—Black and white, Indian and Mexican American—in a massive march on Washington that would not only coincide with the days of protest against the Vietnam War, but also promised to continue till the whole white power structure was disrupted; civil disobedience that would peacefully revolutionize society by masses in motion. Thereby Dr. King courted death.

It was not King who was the “obstacle” to Black liberation. It was the capitalistic system. The “guerrillas” had far less a revolutionary perspective with their smaller goals and elitist concepts. Whether the march would have developed to keep things moving, to bring “orderly” government to a halt, it is impossible now to say. What is clear is that the threat of the march kept the administration on tenterhooks. All sorts of “new politics,” too, was brought in to bring pressure upon King to direct the movement into electoral channels—and he seemed to begin to think in these terms himself.

BLACK AND WHITE

But all was still in flux, masses were in motion if not in the Movement; white labor was forced to help Black labor at least on specific issues, and not only with finances but a promise to bring “thousands” to Memphis! The atmosphere was charged further as it became clear that President Johnson, while declaring for de-escalation [in the Vietnam War], had in fact embarked on the greatest escalation, although within a more “restricted” area.

The civilians who died were not all in Vietnam. One was gunned down in Memphis and 46 more were killed, 2,600 injured and 21,270 arrested in the week of Black revolt that followed King’s assassination.

It is true that all that Dr. King had achieved through the years was but prologue. But it is prologue to a drama of liberation that is unfolding daily. His greatness lay in recognizing the objective movement of history and aligning himself with it. Precisely because it was both objective and had masses in motion, it is sure to continue on a high historic level till society is reconstructed from the bottom up.

[1] Albert B. Cleage Jr. was a Black nationalist minister active in civil rights in Detroit.

[1] The Montgomery, Alabama, Bus Boycott lasted a year, beginning December 1955 after Rosa Parks, an activist and organizer since the 1940s, was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on the bus for a white man. Dr. King rose to prominence after being recruited to lead the boycott.

[3] Marxism and Freedom, from 1776 until Today, by Raya Dunayevskaya (Humanity Books, 2000), p. 281.

[4] “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” April 16, 1963, by Martin Luther King Jr.

[5] See analysis in “New Passions and New Forces,” chapter 9 of Philosophy and Revolution, by Raya Dunayevskaya (Lexington Books, 2003).