From the January-February 2018 issue of News & Letters

CŒUR INDIGNÉ / INDIGNANT HEART

by CHARLES DENBY

Autobiography of a Black American Worker

Translated, presented and annotated

by Camille Estienne

Grandson of slaves, Charles Denby (1907-1983) spent his childhood on a cotton plantation in Alabama before seeking work in the automobile factories of Detroit, Mich., where he became a tough and seasoned union militant. On the plantation, his grandmother told about her memories of times under slavery, Black sharecroppers defended themselves as best they could from the violence of the white landowners, and the young people left for the North where they hoped to escape racism and exploitation.

But in the factories in the North, African Americans were relegated to the hardest, least skilled and lowest-paid jobs—and the union leaders urged them to be patient.

At that point, Denby learned to fight back. In the midst of World War II, he organized a wildcat strike in his shop, which brought him to the attention of Communist militants and some local Trotskyists. The years from 1943 to 1951 were years of political and union apprenticeship—and of direct confrontation with the multiple forms of racism in the factories and political groups.

In 1948 Denby joined members of an opposition faction which would soon break with Trotskyism: the Johnson-Forest Tendency. Johnson was the pseudonym of the West Indian intellectual and militant C. L. R. James (1901-1989) who had lived in the U.S. since 1938; Forest was Raya Dunayevskaya (1910-1987), a militant socialist born in what is now Ukraine, who had briefly been the secretary of Leon Trotsky in Mexico in 1937-38. The small group that assembled around them developed a critical analysis of the realities of production relations in the Soviet Union and called into question the necessity of a party of professional revolutionaries.

PLANTATION WORLD BROUGHT TO LIFE

In many respects, the evolution of the Johnson-Forest Tendency resembles that of the French group Socialism or Barbarism, which came into being during the same period of time. Along the same lines as Marx’s 1880s “A Workers’ Inquiry,” the American group strove to bring forth the testimony from different elements that make up the working class, and Denby was encouraged to tell of his experiences as a Black worker.

In many respects, the evolution of the Johnson-Forest Tendency resembles that of the French group Socialism or Barbarism, which came into being during the same period of time. Along the same lines as Marx’s 1880s “A Workers’ Inquiry,” the American group strove to bring forth the testimony from different elements that make up the working class, and Denby was encouraged to tell of his experiences as a Black worker.

In the first part of his memoir/journal, published in 1952 under the pseudonym of Matthew Ward, Denby forcefully brought to life the details of the world of the plantation that was at the same time violent and full of solidarity, before he told of his many experiences as an African-American worker in the segregationist South and in the industrial North. Whether it was about a cotton plantation in the early 1900s, an automobile manufacturing plant in the 1920s, the city of Montgomery in the 1930s, or a war industry factory in the 1940s, Denby, without any trace of self-pity, evokes these worlds where racial oppression and economic exploitation reigned supreme.

With the talent of a storyteller that makes us feel nourished with a rich oral tradition, he chronicles the multiple acts of more or less open resistance by which the exploited fought back. Certain stories have undoubtedly been told more than once, and the listeners must have rejoiced, as do we, about the tricks played here and there by those who have nothing in common with those who see themselves as all-powerful.

THE NEW WORLD OF THE MOVEMENT

The second part of the book, published in 1978 along with the 1952 text, brings us into a new world. The first chapters tell of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the starting point of the African-American Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. These pages echo the colorful storytelling that Denby did in the first part of the book, tell of his own revolt in a bus in Montgomery 20 years earlier. But this time it’s not just a question of an individual and momentary revolt, but of a mass movement of struggle against the entire systems of segregation and discriminatory rules in the Southern states.

From the beginning, Denby deeply committed himself to the movement, returning to the South whenever he could, meeting with Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks and many who remain anonymous, and whose acts of courage called into question all aspects of a system of oppression in secular life.

In 1955 Denby became the editor-in-chief of a workers’ newspaper, News & Letters, in which, all through the 1950s and 1960s, he brought to light the struggles of the Black liberation movement and its internal debates.

As a production worker in the automobile industry until his retirement in 1972, he attentively observed the consequences of automation on working conditions in the factory and the workers’ forms of revolt against the greater and greater constraint and submission of the human being to the machine.

In 1973, as in 1943, he is on the side of those for whom revolt translates into wildcat strikes, strikes that escaped the control of the labor bureaucracy, against which he never ceased to fight.

Indignant Heart is a remarkable testimony on the life and the struggles of African-American workers in the 20th Century.

—Announcement translated by D. Chêneville

Collection Voix d’en Bas (voices from below)

from Editions Plein Chant, 35 route de Conde, 16120 Bassac, France. www.pleinchant.fr

ISBN 978-2-85452-334-8

♦♦♦

Excerpts from Indignant Heart: A Black Worker’s Journal

MONTGOMERY 1955

I decided to go back to the South when so many new developments were taking place among the Blacks following the 1954 Supreme Court decision outlawing school segregation and the 1955 murder of the Black youth Emmett Till in Mississippi.

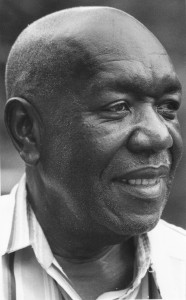

Charles Denby, author of Indignant Heart: A Black Worker’s Journal. Photo by Allen Willis (John Alan) for News & Letters.

A lot of tension was building up, and nobody knew where or when it would break. And on December 5, 1955, there wasn’t a soul who thought that when a working woman, a seamstress named Rosa Parks, refused to give up her seat to a white man on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, that the break had come. Each concrete act took everyone by complete surprise, from the refusal by Mrs. Parks to give up her seat to a white man, to the response to her arrest and court appearance, to the mass demonstrations led by the then unknown Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., to the Black community running their own transportation system. It became Revolution, a word none of us ever used referring to an action defying the segregated conditions of life in the South. That mass action of revolt was the Montgomery Bus Boycott…

But after [80% of] the Blacks boycotted the buses that Wednesday, and then went back to the bus stops on Thursday, all the bus drivers—and they were all white then—would pull up to a stop and, where there were all Blacks standing there, went on by without picking up a single one of them.

The reaction of the Blacks was, “…We walked yesterday, we can walk today.” And that, Rev. King said, was the beginning of the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

LOWNDES COUNTY, ALABAMA 1965

To order your copy of Indignant Heart: A Black Worker’s Journal, click here.

When the marchers went through Lowndes County in the 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery…there had never been a single Black registered to vote. The whites had the Blacks in Lowndes County so suppressed that they told them if they tried to join the march, they’d be run off the land and out of the area…From that point, the march from Selma to Montgomery, the Blacks in the whole of Lowndes County began to organize—in that same week…

And when the Blacks learned after the march that Mrs. Viola Liuzzo, the Michigan wife of a Teamster union official who had come down to join in the march, had been murdered for joining the freedom struggle, they just became transformed. Nobody could see it then, but Mrs. Liuzzo’s actions, aimed at trying to change the conditions in the U.S. so life would be based on human relations, was the same basis that produced the women’s liberation movement a few years later.

A truckload of Blacks went to the Selma courthouse and demanded to be registered to vote. Included were many prominent Blacks in Lowndes County, who declared that they didn’t want any more nonsense about how many bubbles there are in a bar of soap. (This was one of the questions asked of Blacks in Mississippi to disqualify them from voting.) And they registered for the first time in Lowndes County.

Indignant Heart is also in German:

Im Reichsten Land der Welt–Indignant Heart in German

The German publisher RotbuchVerlag Berlin published the German translation of Indignant Heart during Charles Denby’s lifetime, in 1981, under the title Im reichsten Land der Welt: Ein schwarzer Arbeiter erzählt sein Leben, or In the Richest Country in the World: A Black Worker Tells his Life Story.