Editor’s note: For the centenary year of V.I. Lenin’s death, we present in three parts Raya Dunayevskaya’s “Hegelian Leninism,” presented on October 10, 1970, at the first international Telos Conference. Unlike most of the commentary marking the centenary, this piece focuses on the centrality of the Hegelian dialectic to Lenin’s contribution for his time and ours. The three sections are titled “The Dialectic Proper,” with which we begin here, followed by “Dialectics of Liberation” and “Death of the Dialectic.” The whole piece was published in chapter 1 of Russia: From Proletarian Revolution to State-Capitalist Counter-Revolution: Selected Writings by Raya Dunayevskaya (Haymarket Books, 2018).

“The group of editors and contributors of the magazine Under the Banner of Marxism should, in my opinion, be a kind of ‘Society of Materialist Friends of Hegelian Dialectics.’”

Lenin, 1922

During the disintegration of the entire world and of established Marxism in the holocaust of World War I, Lenin encountered Hegel’s thought. The revolutionary materialist activist theoretician, Lenin, confronted the bourgeois idealist philosopher Hegel who, working through two thousand years of Western thought, revealed the revolutionary dialectic. In the shock of recognition Lenin experienced when he found the revolutionary dialectic in Hegel, we witness the transfusion of the lifeblood of the dialectic, the transformation of reality as well as thought: “Who would believe that this—the movement and ‘self-movement’. . . spontaneous, internally-necessary movement. . . ‘movement and life’ is the core of ‘Hegelianism,’ of abstract and abstruse (difficult, absurd) Hegelianism??”[1]

“The Dialectic Proper”

V.I. Lenin

Lenin the activist, Party man and materialist underwent “absolute negativity.” While reading “The Law of Confrontation” he concluded his new appreciation of the dialectic by saying:

the principle of all self-movement: The idea of universal movement and change (1813 Logic) was conjectured before its application to life and society. In regard to society it was proclaimed earlier (1847) than it was demonstrated in application to man (1859).[2]

The illumination cast here on the relationship of philosophy to revolution in Lenin’s day is so strong that today’s challenges become transparent and reveal the ossification of philosophy and the stifling of the dialectics of liberation. Russian philosophers refuse to forgive Lenin for this. Their underhanded criticism of his Philosophic Notebooks continues unabated even on the hundredth anniversary of his birth. They have blurred the distinction between the vulgar materialist photocopy theory of Materialism and Empirio-Criticism (1908) and Lenin’s totally new philosophical departure in 1914 toward the self-development of thought.

In the Notebooks, Lenin wrote: “Alias: Man’s cognition not only reflects the objective world, but creates it.”[3] B.M. Kedrov, director of the Institute of History of Science and Technology, reduces Lenin’s new appreciation of “idealism” to philistine semantics:

What is fundamental here is the word ‘alias,’ meaning otherwise or in other words, followed by a colon. This can only mean one thing, a paraphrase of the preceding note on Hegel’s views. . . If the meaning of the word ‘alias’ and the colon following it are considered, it will doubtless become clear that in that phrase Lenin merely set forth, briefly, the view of another, not his own.”[4]

Professor Kedrov’s zeal to deny Lenin’s 1914 Notebooks “are in fundamental contravention of Materialism and Empirio-Criticism” has led him to such cheap reductionism that “in defense” of Lenin, Kedrov can only attribute to Lenin his own philistinism: “Lenin categorically rejects and acidly ridicules the slightest slip by Hegel in the direction of ascribing to an idea, to a thought, to consciousness the ability to create the world”[5] With this single stroke, Kedrov deludes himself into believing he has closed the philosophic frontiers Lenin opened.

The West’s deafness to Lenin’s break with his philosophic past (in which cognition had only the role of “reflecting” the objective or the material) has produced an intellectual incapacity to cope with Communist emasculation of Lenin’s philosophy.[6] However, anyone who invokes Lenin’s name “favorably” should at least remember either “the objective world connection” to which Lenin incessantly referred or men’s “subjective” aspirations, the phrase by which Lenin “translated” his concept of consciousness “creating the world”: “the world does not satisfy man and man decides to change it by his activity.”[7] Even independent Marxists have been sucked into the theoretical void following Lenin’s death and have lazily avoided the rich, profound, concrete Notebooks. They bemoan the “jottings” which make the Notebooks seem so “scanty” that any attempt to understand them could only be “idle speculation.” Sticking to “provable” politics as if that were sufficient, they call for “application” of the dialectic. No doubt, the proof of the pudding is always in the eating, and Lenin’s “application” of the Notebooks was in politics. But were we to begin there and dwell on politics apart from Lenin’s new comprehension of the dialectic, we would understand neither his philosophy nor his politics. It is the interaction of the two which is relevant today.

During the critical decade of war and revolution between 1914 and 1924, Lenin did not prepare the Notebooks for publication. However, his heirs had no legitimate reason to delay their publication until six years after his death. When they were published in 1929-1930, neither Trotsky, Stalin, Bukharin, nor “mere academicians” (whether mechanists or “dialecticians”) took them seriously.[8] A new epoch of world crises and revolutions and the birth of the Black dimension in Africa and the U.S. finally compelled an English publication in 1961.

Lenin began reading Hegel’s Science of Logic in September, 1914, and finished on December 17. Even from his comments on the Prefaces and the Introduction, it is clear that Lenin’s concrete concerns (to which he referred in his “asides” as he copied and commented on quotations from Hegel) were “the objective world connections,” the Marxists and the Machists, and above all Marx’s Capital. Reading Hegel’s Introduction, in which he speaks of logic as “not mere abstract Universal, but as a Universal which comprises in itself the full wealth of Particulars” [SLI, p. 69], Lenin wrote:

Lenin began reading Hegel’s Science of Logic in September, 1914, and finished on December 17. Even from his comments on the Prefaces and the Introduction, it is clear that Lenin’s concrete concerns (to which he referred in his “asides” as he copied and commented on quotations from Hegel) were “the objective world connections,” the Marxists and the Machists, and above all Marx’s Capital. Reading Hegel’s Introduction, in which he speaks of logic as “not mere abstract Universal, but as a Universal which comprises in itself the full wealth of Particulars” [SLI, p. 69], Lenin wrote:

1.Capital. A beautiful formula: ‘not a mere abstract universal, but a universal which comprises in itself the wealth of particulars, individual, separate (all the wealth of the particular and separate)!! Trés Bien!”[9]

No matter how often Lenin reminded himself that he was reading Hegel “materialistically,” no matter how he lashed out against the “dark waters” of such abstractions as “Being-for-Self” and despite the fact that in his first encounter with the categories of the Doctrine of Notion (Universal, Particular, Individual) he called them “a best means of getting a headache,” Lenin grasped from the outset not only the deep historical roots of Hegel’s philosophic abstractions but also their historical meaning for “today.” Therefore, Lenin sided with Hegel’s idealism against what he called the “vulgar materialism” of his day:

The idea of the transformation of the ideal into the real is profound. Very important for history—Against vulgar materialism. NB. The difference of the ideal from the material is also not unconditional, not excessive (überschwenglich).”[10]

The significance of Lenin’s commentary is that he made it while he was still reading the Doctrine of Being. To all Marxists after Marx, including Engels,[11] the Doctrine of Being had meant only immediate perception, or the commodity, or the market, i.e., the phenomenal, apparent reality as against the essential exploitative relations of production. Even here, Lenin escaped “vulgar materialism,” which sought to erect impassable barriers between the ideal and the real. In Lenin’s new evaluation of idealism, however, there was neither “sheer Hegelianism” nor “pure” Maoist voluntarism.[12] Instead Lenin’s mind was constantly active, seeing new aspects of the dialectic at every level, whether in Being or in Essence. Indeed, in the latter sphere Lenin emphasized not the contrast between Essence and Appearance, but instead self-movement, self-activity, and self-development. For him it was not so much a question of essence versus appearance as it was of the two being “moments” (Lenin’s emphasis) of a totality from which even cause should not be singled out: “It is absurd to single out causality from this. It is impossible to reject the objectivity of notions, the objectivity of the universal in the particular and in the individual.”[13] Reading the Doctrine of Notion, Lenin broke with his philosophic past. The break began in the Doctrine of Essence, at the end of Causality, when he began to see new aspects of causality and of scientism, which could not possibly fully explain the relationship of mind to matter. Therefore, he followed Hegel’s transition to the Doctrine of Notion, “the realm of Subjectivity, or Freedom” which Lenin immediately translated as “NB Freedom = Subjectivity (‘or’) End, consciousness, Endeavor, NB.”[14]

Lenin was liberated in his battles with the categories of the Doctrine of Notion, the very categories he had called “a best way of getting a headache.” First, he noted that Hegel’s analysis of these categories is “reminiscent of Marx’s imitation of Hegel in Chapter I.”[15] Second, Lenin no longer limited objectivity to the material world but extended it to the objectivity of concepts: freedom, subjectivity, notion. These are the categories through which we gain knowledge of the objectively real. They constitute the beginning of the transformation of objective idealism into materialism. By the time he reached Hegel’s analysis of the relationship of means to ends, he so exulted in Hegel’s genius in the dialectic, “the germs of historical materialism,”[16] that he capitalized, boldfaced, and surrounded with three heavy lines Hegel’s statement that “in his tools man possesses power over external Nature even though, according to his ends, he frequently is subjected to it.”[17] In reaching that conclusion, Lenin had projected his new understanding of objectivity by writing:

Just as the simple value form, the individual act of exchange of a given commodity with another, already includes, in undeveloped form, all major contradictions of capitalism,—so the simplest generalization, the first and simplest forming of notions (judgments, syllogisms, etc.) signifies the ever-deeper knowledge of the objective world connections. It is necessary here to seek the real sense, significance, and role of the Hegelian Logic. This NB. [18]

Thirdly, Lenin began striking out not only against Hegel but against Plekhanov and all Marxists including himself. Although Moscow’s English translator omitted the emphasis in “Marxists,” there is no way to modify Lenin’s conclusion that

none of the Marxists understood Marx. It is impossible fully to grasp Marx’s Capital, especially the first chapter, if you have not studied through and understood the whole of Hegel’s Logic.”[19]

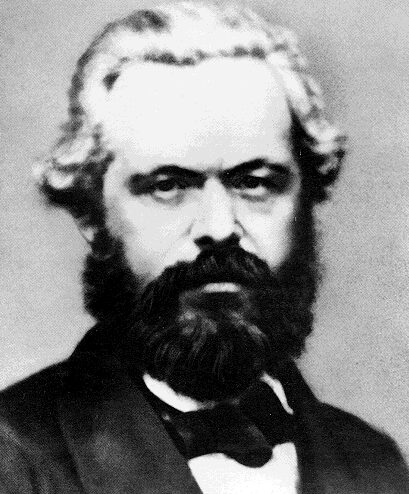

Karl Marx

Naturally, like the aphorism on “cognition creating the world,” this cannot be taken literally. Long before Lenin seriously studied the Logic, no one had written more profoundly on economics, especially on Volume II of Capital, both as theory and as the concrete analysis of The Development of Capitalism in Russia. Nevertheless, the world had changed so radically by the outbreak of World War I and the collapse of the Second International that Lenin became dissatisfied with everything Marxists had written before 1914 on economics, philosophy, and even revolutionary politics. These writings lacked the sharpness and the necessary absolutes of his dictum, “Turn the imperialist war into a civil war.” Of course, Lenin did not bring a blank mind to the study of Science of Logic. Even as a philosophical follower of Plekhanov, who never understood “the dialectic proper,”[20] Lenin was a practicing dialectician. The actual contradictions in Tsarist Russia prepared him for these new conceptions of the dialectic, the “algebra of revolution,” which he now began to spell out as “subject” (masses) reshaping history. As Lenin prepared himself theoretically for revolution, dialectics became pivotal and ever more concrete to him. He had begun the study of the Logic in September, 1914, at the same time he completed the essay “Karl Marx” for the Encyclopedia Granat. Lenin was not fully satisfied with what he had written when he finished the Logic on December 17, 1914. On January 5, 1915, with the world war raging, he asked Granat if he could make “certain corrections in the section on dialectics. . . . I have been studying this question of dialectics for the last month and a half, and I could add something to it if there was time. . . .”[21] By pinpointing the time as a “month and a half,” Lenin indicated the specific book, Subjective Logic, which had opened his mind to new philosophical frontiers. The Notebooks themselves, of course, make clear beyond doubt that it was while reading the Doctrine of Notion, directly after the section of the Syllogism, that Lenin exploded with criticism of turn-of-the-century Marxists for having made their philosophic analyses “more in a Feuerbachian and Buchnerian than in a Hegelian manner,” and with the realization that it was “impossible fully to grasp Marx’s Capital, especially the first chapter, if you have not studied through and understood the whole of Hegel’s Logic.”[22]

The Russians ignore that Lenin not only concentrated on Subjective Logic as a whole but also devoted fifteen pages to the final chapter, the Absolute Idea. But they have to acknowledge that “Lenin evidently assigned great significance to Hegel’s Subjective Logic, since the greater part of his profound remarks and interesting aphorisms are expressed during the reading of this part of the Logic.”[23] But in the three decades since the first publication of the Notebooks, Russian philosophers have not drawn any conclusions from this fact; much less, in their favorite phrase, have they “applied” it. Instead, they have taken advantage of Lenin’s philosophic ambivalence and have refused to see his philosophic break in 1914 with his Plekhanovist past. Certain facts, however, are stubborn. One such fact is that whereas Plekhanov, the philosopher of the Second International, reverted to the materialists of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Lenin eventually came to concentrate on Hegel. Lenin regarded Hegel as crucial to the task of the Russian theoreticians. Lenin saw the need to “arrange for the systematic study of Hegelian dialectics,” which, though it was to be done from a materialist standpoint, was not to be reduced to mere interpretation. Also, it was necessary to “print excerpts from Hegel’s principal works.”[24]

Another stubborn fact is that Lenin’s advice to Russian youth to continue studying Plekhanov cannot alter the task he set for himself:

Work out: Plekhanov wrote probably nearly 1,000 pages (Beltov + against Bogdanov + against Kantians + basic questions, etc. etc. on philosophy (dialectic). There is in them nil about the Larger Logic, its thoughts (i.e., dialectic proper, as a philosophic science) nil!”[25]

The third stubborn fact which Communist philosophers disregard is the significance of Lenin’s swipe (which included Engels) at “inadequate attention” to dialectics as the unity of opposites. “The unity of opposites is taken as the sum total of examples (‘for example, a seed,’ for example, primitive Communism).”[26] Lenin forgave Engels this defect because he wrote deliberately for popularization. However, this cannot touch the deeper truth that, although he always followed Marx’s principle that “it is impossible, of course, to dispense with Hegel,” Engels considered that “the theory of Essence is the main thing.”[27] Lenin, on the other hand, held that the Doctrine of Notion was primary because, at the same time that it deals with thought, it is concrete. It is subjective, not merely as against objective but as a unity in cognition of theory and practice. Through the Doctrine of Notion, Lenin gained a new appreciation of Marx’s Capital, not merely as economics but as logic. Lenin now called Capital “the history of capitalism and the analysis of the notions summing it up.”[28] Lenin, and only Lenin, fully understood the unity of materialism and idealism present even in Marx’s strictly economic categories.

Marx founded historical materialism and broke with idealism. But he credited idealism rather than materialism for developing the “active side” of “sensuous human activity, practice.”[29] On the road to the greatest material (proletarian) revolution, Lenin likewise saw the indispensability of the Hegelian dialectic. He summarized in an article what he had just completed in the Notebooks: “Dialectics is the theory of knowledge of (Hegel and) Marxism. This is the ‘aspect’ of the matter (it is not ‘an aspect’ but the essence of the matter) to which Plekhanov, not to speak of other Marxists, paid no attention.”[30] Having reestablished continuity with Marx and Hegel, Lenin fully grasped what was new in Marx’s materialism: its human face. He was not, of course, familiar with the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, in which Marx defined his philosophy as “a thoroughgoing naturalism or humanism.”[31]

At the opposite pole stand the official Russian philosophers. There is, of course, nothing accidental about this situation: it has deep, objective, material roots. It is outside the scope of this article to discuss the transformation of the first workers’ state into its opposite, state-capitalism.[32] What must be stressed is the new quality which Lenin discerned in the dialectic. Because he lived in a historical period entirely unlike Engels’, Lenin did not stop at essence versus appearance but proceeded to the Doctrine of Notion. Because the betrayal of socialism came from within the socialist movement, the dialectical principle of transformation into opposite, the discernment of counterrevolution within the revolution, became pivotal. The uniqueness of dialectics as self-movement, self-activity, and self-development was that it had to be “applied” not only against betrayers and reformists but also in the criticism of revolutionaries who regarded the subjective and the objective as separate worlds. Because “absolute negativity” goes hand in hand with dialectical transformation into opposite, it is the greatest threat to any existing society. It is precisely this which accounts for the Russian theoreticians’ attempt to mummify rather than develop Lenin’s work on the dialectic. They cannot, however, bury Lenin’s panegyric to the dialectic: “the living tree of living, fertile, genuine, powerful, omnipotent and absolute human knowledge.”[33]

The contradictory jamming up of the opposites, “absolute” and “human,” is true. Toward the end of Science of Logic, Lenin stopped shying away from “Absolute” and grasped that the true “Absolute” is “absolute negativity.” Absolute lost its godlike fetishism and revealed itself as the unity of theory and practice. The dialectical development through contradiction, which is an “endless process, where not the first but the second negativity is the ‘turning point,’ transcends opposition between Notion and Reality.” Since this process “rests upon subjectivity alone,”[34] Lenin adds, “This NB: The richest is the most concrete and most subjective.”[35] These are the actual forces of revolution, and we will now turn to the dialectics of liberation just as Lenin turned then to the practice of dialectics.

Continued in section 2, “Dialectics of Liberation”…

[1]. The first English translation of Lenin’s Abstract of Hegel’s Science of Logic appeared as Appendix A of my Marxism and Freedom (New York, 1958). This translation will hereafter be referred to as M&F. I will also cite parallel passages in the Moscow translation (Lenin, Collected Works, Vol. 38, 1961). Here, see M&F, p. 331; LCW 38, p. 141. [Since the translation was dropped in later editions of M&F, we provide page numbers for Russia: From Proletarian Revolution to State-Capitalist Counter-Revolution: Selected Writings by Raya Dunayevskaya (Haymarket Books, 2018). In this instance, p. 84. —ed.]

[2]. Ibid. In this quotation, the date 1847 refers to the writing of The Communist Manifesto, which, however, was published only in 1848. The date 1859 is the date of the publication of Darwin’s Origin of the Species.

[3]. M&F, p. 347; LCW 38, p. 212; Russia, p. 100.

[4]. B.M. Kedrov, “On the Distinctive Characteristics of Lenin’s Philosophic Notebooks,” Soviet Studies in Philosophy (Summer, 1970).

[5]. Ibid.

[6]. Professor David Joravsky senses that Lenin’s comments on Hegel’s Science of Logic are “tantalizingly suggestive of a new turn in his thought” in Soviet Marxism and Natural Science, 1917-1932 (New York, 1961), p. 20. He exposes Stalin’s transformation of Lenin’s alleged “partyness” in the field of philosophy into pure Stalinist monolithism. Nevertheless, by excluding from his own work a serious analysis of Lenin’s Philosophic Notebooks, Joravsky leaves the door wide open for lesser scholars to write as if there were a straight line from Lenin to Stalin instead of a transformation into opposite. As for Lenin’s Materialism and Empirio-Criticism, Lenin himself was the one who stressed its political motivations. He wrote in his letter to Gorky, “The Mensheviks will be reduced to politics and that is the death of them.” See the chapter “Lenin and the Partyness of Philosophy” in Joravsky’s work.

[7]. LCW 38, p. 213.

[8]. The first publication of the Philosophic Notebooks was edited by Bukharin, who, however, had nothing to say about it. The Introduction of 1929 by Deborin and that of 1930 by Adoratsky appeared only in the Russian edition. See Leninski Sbornik (Moscow), Vol. XII. It is also worthwhile to consult Joravsky, op. cit., pp. 97ff., regarding Bukharin and Trotsky on the Philosophic Notebooks.

[9]. M&F. p. 328; LCW 38, p. 99; Russia, p. 81.

[10]. M&F, p. 329; LCW 38, p. 124; Russia, p. 82.

[11]. The two letters of Engels to Conrad Schmidt dated November 1, 1891, and February 4, 1892, are most applicable: Engels cited “a good parallel” between the development of Being into Essence in Hegel and the development of commodity into capital in Marx.

[12]. The pretentious French Communist Party philosopher Louis Althusser is working hard to kill the dialectic and at the same time to present himself as a “Leninist.” But such absolute opposites cannot coexist, not even when one is inventive enough to add Mao and Freud to the hodgepodge. See especially his lecture to bourgeois French philosophers, since reproduced as a pamphlet, Lenine et la Philosophie (Paris, 1968).

[13]. M&F, p. 339; LCW 38, p. 178; Russia, p. 92.

[14]. M&F, p. 336; LCW 38, p. 164; Russia, p. 89.

[15]. M&F, p. 339; LCW 38, p. 178; Russia, p. 92.

[16]. M&F, p. 342; LCW 38, p. 189; Russia, p. 95.

[17]. SLII, p. 338.

[18]. M&F, p. 339; LCW 38, p. 179; Russia, p. 92.

[19]. M&F, p. 340; LCW 38, p. 180; Russia, p. 93.

[20]. M&F, p. 354; LCW 38, p. 277; Russia, p. 107. Cf. “On Dialectics,” in Vol. 38.

[21]. The Letters of Lenin (New York, 1937), p. 336.

[22]. M&F, p. 340; LCW 38, p. 180; Russia, p. 93.

[23]. Leninski Sbornik, op. cit., Introduction by Deborin to Vol. IX.

[24]. Lenin, Selected Works (New York, 1943), Vol. IX, p. 77.

[25]. M&F, p. 354; LCW 38, p. 277; Russia, p. 107.

[26]. Lenin, Selected Works, op. cit., Vol. XI, p. 81. “On Dialectics” also appears both in Vol. 38 of the Collected Works and in Selected Works, Vol. XIII (1927), as an addendum to Materialism and Empirio-Criticism. It is also wrongly attributed there to “sometime between 1912 and 1914.”

[27]. Engels to Conrad Schmidt, November 1, 1891.

[28]. M&F, p. 353; LCW 38, p. 320; Russia, p. 106.

[29]. I have used the latest Moscow translation of the “Theses on Feuerbach” in Marx and Engels—The German Ideology (1964), pp. 645 and 647.

[30]. LCW 38, p. 362.

[31]. [From “Critique of the Hegelian Dialectic,” as translated by Dunayevskaya, in Marx’s Philosophy of Revolution in Permanence for Our Day (Haymarket Books, 2019), p. 347, originally published in M&F, p. 313.]

[32]. See chapter 13, “Russian State Capitalism vs. Workers” Revolt,” M&F. For the development of the state-capitalist theory from its birth in 1941 until the present, see the Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Raya Dunayevskaya Collection, Wayne State University. [See https://rayadunayevskaya.org for the online archives.]

[33]. LCW 38, p. 363.

[34]. SLII, p. 447.

[35]. LCW 38, p. 232.