From the September-October 2015 issue of News & Letters

Editor’s note: To highlight the new online availability of the Raya Dunayevskaya Collection at www.rayadunayevskaya.org, we present excerpts of her Report on Marxist-Humanist Perspectives given Aug. 31, 1985 (#10348 in the Collection). Here she takes up the development of the Marxist-Humanist concept of Archives out of the category made of the totality of Marx’s Archives as a new beginning for today.

by Raya Dunayevskaya

[S]eeing Marx’s works as a totality, especially the “new moments” in the works of his last decade, set a new task for future generations to work these out for their age. For Marxist-Humanists, that also illuminated the Marxist-Humanist Archives, because it set, in a totally new context, what is meant by catching the link of continuity with Marx’s Marxism, as well as revealing that the discontinuity of an age, a century later, is no barrier to catching the continuity. Marxist-Humanism’s Archives demonstrate that. It continues to motivate all our writings and activities.

KEY IS THE PROCESS OF DEVELOPMENT

Let’s now turn to the process of development of Marxist-Humanism in its three major philosophic works. The movement from practice that is itself a form of theory so predominated News and Letters Committees’ first period of development, culminating in the publication of my first book, Marxism and Freedom, that that work extended the expression “movement from practice” (if going back into history can be called an extension) and disclosed that it characterized human development before Marx.

It is true that Marx alone rooted his entire discovery of a new continent of thought and of revolution in that movement from below. It is also true that the maturity of our age led us to make a category of that movement from practice. Nevertheless, strange as it may seem to talk of “unconsciousness” when speaking of Hegel, it is a fact that the movement from practice—in his period, the French Revolution—inspired Hegel to break with all previous philosophies. It demonstrates that the revolutionary nature of the dialectic methodology was by no means limited to where Kant “stopped dead” in his modalities. On the contrary, dialectic methodology was the way philosophy would reflect and “transcend” reality.

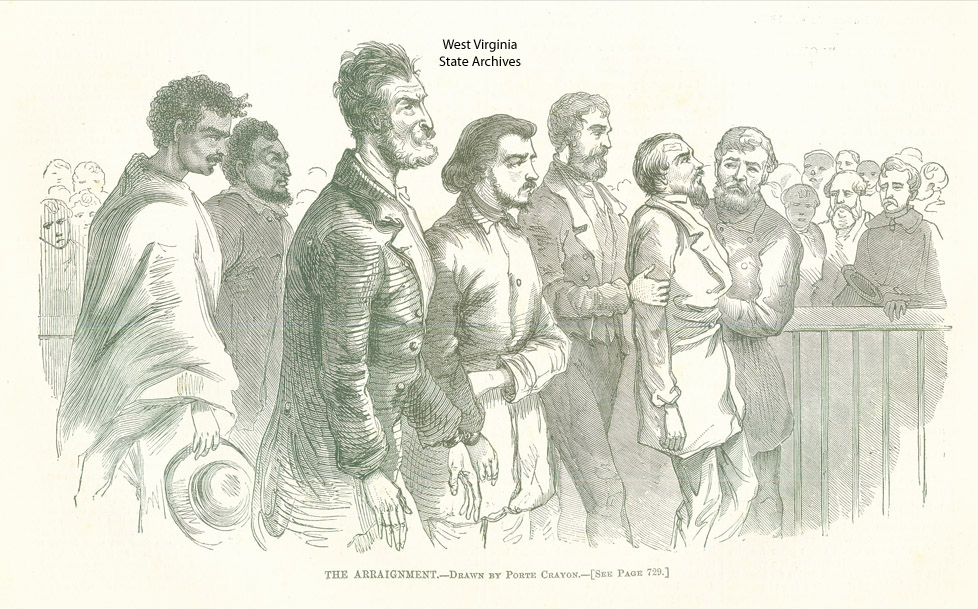

John Brown and collaborators in a portrait by David Hunter Strother, AKA Porte Crayon, drawn at the time titled “The Arraignment.”

It was true of the Abolitionist activities, which included John Brown and Bloody Kansas, culminating in John Brown’s attack on Harpers Ferry. This, Marx concluded, signaled the start of the Civil War in the U.S. It was Marx who had held, in his Preface to Capital:

“Just as in the 18th century, the American War of Independence sounded the tocsin for the European middle class, so in the 19th century the Civil War did the same for the European working class.” (He was referring, of course, to the French Revolution in the first case and the First International Workingmen’s Association in the second.)

THE MOVEMENT FROM PRACTICE…

We discovered the movement from practice in 1953 when we first broke through the mystical shroud Hegel had thrown over Absolute Idea in his mystically expressed “unity of theory and practice.” Out of that movement, which demonstrated itself as a form of theory, the historic-dialectic structure of Marxism and Freedom was created.

It also dictated the context in which we presented Lenin’s break from his previous concept of the dialectic. His 1914 concept of the revolutionary nature of the dialectic separated the methodology of his attack on the betrayal of the Second International from that of all other revolutionaries, and governed his call for turning “the imperialist war into civil war.” His practice of the dialectic of thought as well as of revolution underlined his call for a Third International.

…IS ITSELF A FORM OF THEORY

There was an attempt by many of the non-Stalinist Left to make our new category of the “movement from practice” merely an “update” they did not need. It took very nearly a whole decade in which we let all the new voices from below be heard—from Workers Battle Automation and Freedom Riders Speak for Themselves to The Free Speech Movement and the Negro Revolution, the “Weekly Political Letters from West Africa” as well as Notes on Women’s Liberation: We Speak in Many Voices. It took witnessing the aborted revolutions of 1968, which had operated with [then radical activist] Daniel Cohn-Bendit’s concept of the sufficiency of catching theory “en route,” to finally force the wholly new and original development of “Absolute Negativity as New Beginning.” This was finally recognized as very far from a mere “update.”

RELATION OF OBJECTIVE TO SUBJECTIVE (OR) A NEW BEGINNING FROM MARXISM

I had, way back in 1960, written to Herbert Marcuse on the Absolute Idea and liberation movements in the emergence of a Third World. I called these “random thoughts” a corollary to Marxism and Freedom. What I kept developing in these “random thoughts,” not by any means all addressed to Herbert Marcuse, was the relationship of objective to subjective, notion to reality. I insisted that even that had not exhausted the tasks of revolutionaries, who must interpret Marxism for their own age—that it is they who must chisel out from totality itself a new beginning. It was 1973 before this was fully worked out as Philosophy and Revolution, from Hegel to Sartre and from Marx to Mao.

ABSOLUTE NEGATIVITY AS NEW BEGINNING

That work began with “Why Hegel? Why Now?” presenting Absolute Negativity as New Beginning and thus, in the very first chapter, hewing out also a “new Hegel”—that is, this age’s reinterpretation of Hegel that no others had done, and at the same time, detailing seriously Marx’s roots, as well as Lenin’s “Shock of Recognition.”

Part II of Philosophy and Revolution then faced “Alternatives”—other revolutionaries such as Trotsky, and Mao as well as “Sartre, the Outsider Looking In.” Only after the new on the Hegelian Dialectics of our age and only after Marx and Lenin, did I turn to the rise of a “new Humanism” in East Europe and in Africa, especially in the writings of Frantz Fanon, in Part III, against the background of the objective world of state-capitalism in their lands. Only then did we turn, in the final Chapter 9, to the “New Passions and New Forces” of the 1960s. Whether as in the first chapter of Philosophy and Revolution, or in the academic form in which I presented it to the Hegel Society of America, the point was that “Absolute Idea as New Beginning” could not be left in a “general” state, but had to be made concrete for one’s own age.

The events of the 1970s were by no means limited to President Richard Nixon’s Pax Americana and the then still-continuing Vietnam War, which shook the world. At one and the same time, Mao initiated two absolute opposite events in his last period—the chaotic activities of his Red Guards on the one hand, and rolling out the red carpet for Nixon-Kissinger, on the other. Nixon’s political horrors no sooner ended than the world was confronted by so deep and so new a stage of global economic crisis that it brought about structural changes in the so-called private capitalist orbit. Instead of that succeeding in finally shaking up post-Marx Marxists, they continued their non-comprehension of Marx’s greatest work, Capital. It is this that led to a new pamphlet by us [Marx’s Capital and Today’s Global Crisis] on Today’s Global Crisis, Marx’s Capital, and the Marxist Epigones Who Try to Truncate It.

NEW MOMENTS IN MARX’S LAST DECADE

Far, however, from only counter-revolution continuing its dominance, great new revolutionary awakenings were emerging, including the revolutionary force of Women’s Liberation becoming a Movement, as well as new revolutionary upsurges in what was fascist Portugal, initiated from Africa, and in the Shah’s Iran. They coincided with the transcription at long last of Marx’s Ethnological Notebooks. These opened for us the “new moments” Marx experienced in his last decade, which disclosed a new trail from his 1880s to our 1980s. Marx’s Archives, the view of his work as a totality, revealed a new concept Marx had of objectivity, which included the development of the masses in motion. It created a new way to look at our Marxist-Humanist Archives.

In summation: the 1970s called for a balance sheet of all post-Marx Marxists, beginning with Engels and continuing to our age. Though Engels’ first book after the death of Marx—his Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State—disclosed how far apart were Marx’s and Engels’ views on the “Woman Question,” this was by no means the only dialectical difference between them. The most critical and all-sided divergence was Marx’s multilinear view of human development vs. Engels’ unilinear view.

It is true that Lenin opened a Great Divide in post-Marx Marxism. His actual practice of the dialectics of revolution succeeded in achieving the only successful proletarian revolution in history. Anyone who attempts to skip over that Great Divide does it at his peril. It remains the ground, but ground is not the whole. It is neither a sum total nor totality as new beginning for our age.

FORM OF ORGANIZATION NOT THE ANSWER

The revolutionary theoretician, Rosa Luxemburg, was right in pointing to the question of the needed new relationship of spontaneity to the Party, and insisting on the uniqueness of revolutionary democracy continuing the “day after” and not only the “day before” and “day of” revolution. It is this question that became a focal point of Marxist-Humanism’s new work, Rosa Luxemburg, Women’s Liberation, and Marx’s Philosophy of Revolution. At the some time, it became clear that the question of the dialectics of the Party was not approached in full either by Lenin or by Luxemburg. Marxist-Humanists were right when, from the beginning, they broke with Lenin’s concept of “vanguard party.” Luxemburg, too, however, offered no truly fundamental answer with her concept of spontaneity, once she nevertheless remained in the Party. Furthermore, she continued to be totally wrong on the National Question in her concrete opposition to Self-Determination of oppressed nations, placing them as “nationalistic” and bourgeois. In a word, the answer could not be found by remaining on the level only of form of organization.

Rosa Luxemburg

Instead, the imperative need, at the very end of both a learning experience and engaging in a new battle of ideas with such great revolutionaries as Lenin and Luxemburg, was to grapple, all over again, with that missing link of philosophy, the dialectic—the dialectic of revolution, the dialectic of thought, and The Dialectic of the Party (the subject of our new new-book-to-be).

That missing link had plagued post-Marx Marxism ever since the death of Marx in 1883 until Lenin’s rediscovery, at the outbreak of World War I, of Marx’s roots in the Hegelian dialectic, which produced the Great Divide in post-Marx Marxism. Lenin, however, did not show the process of arriving at those great revolutionary conclusions, did not make public his Philosophic Notebooks.

REVOLUTION IN PERMANENCE

After Marxism and Freedom, which first disclosed the Great Divide, and after Philosophy and Revolution, which spelled out Absolute Idea as New Beginning, came the latest grappling with the dialectic in Chapter 11 of Rosa Luxemburg, Women’s Liberation, and Marx’s Philosophy of Revolution, “The Philosopher of Permanent Revolution Creates New Ground for Organization,” which ended with a sum-up of Marx’s theory of permanent revolution, 1843-1883, in the context of this age, on the relationship of organization to philosophy. It disclosed that there was still need of the dialectic as Second Negativity, as the total uprooting. It is that which determined the creation of the final Chapter 12 in that work, on the Trail to the 1980s, which climaxed in a final section, “A 1980s View.”

It is necessary to re-emphasize this. It was only as we were coming to the conclusion of this work and called Marx’s “new moments” the trail to the 1980s that we finally summarized Marx’s Marxism and not only Hegel’s Absolute Idea both as totality and as a new beginning for our age, as organization and philosophy, as dialectics of revolution and of thought, the whole of the dialectic. It spelled out, at one and the same time, that the catching of the continuity with Marx’s Marxism and seeing that the hundred-years’ discontinuity between the ages was Marxist-Humanist continuity or the working out of Marx’s Humanism for our age.

THE NEED FOR THE TOTALITY OF MARX

It is that look at the totality of Marx’s Marxism as new beginning, that new look at Marx’s Archives, that also led us to see the Marxist-Humanist Archives in a new way. It is this discernment which produced the uniqueness of the final, fourth section of Chapter 12—”A 1980s View”….

Thus we express the urgent need to uproot the counterrevolution, whether in the form of Pieter Botha in South Africa or Ronald Reagan in the U.S., so that, roughly, theoretically and practically, that it will create the humus for actual revolution, toward which the American Revolution is most crucial.

Raya stresses here the line of continuity between Marx’s Marxism and Marxist-Humanism: the second is the recreation of the first, for our age.

Marx’s Marxism is a dialectical totality. It carries within the unity of practice and theory, of subjectivity and objectivity, as well as of philosophy and organization.

As Raya tells us here, we can find this same totally developed through the first 35 years of Marxist Humanism (1953-1987, the year of Raya’s death). We can see this development especially in the three main books of the MH body of ideas, as well as in the fourth-to-be.

Marxism and Freedom speaks to us about the essentiality of the revolutionary subjects, their practice itself as a form (a source) of theory. This even applies for Hegel, who wouldn’t have been able to formulate “his” dialectical method without the action of the masses during the French Revolution.

Philosophy and Revolution makes clear that the revolutionary practice of the masses, as crucial as it is, is not enough: we need the union of practice and theory, the Absolute Idea as new beginning, in order to uproot this capitalist society. In her introduction to the book, Raya specifies that the events that triggered its writing were the aborted revolutions of the late 1960s: they showed very concretely that one cannot just “catch theory ‘en route'”.

The third book, Rosa Luxemburg… went further on concretizing the Absolute Idea as new beginning by recreating it in the mass movements of the 1970s: women’s liberation movement, Third World revolutions, etc. At the same time, it opened the door to a dialectical comprehension of revolutionary organization: there are no “private enclaves”; dialectics should also “penetrate” the question of organization. This, in two senses: the spontaneous organizations of the masses, created from below, but also the organization of a small number of activist-thinkers who aid the revolutionary movements to reach their fullest expression.

This is the question Raya didn’t have time to completely develop. But she left the whole body of MH ideas in the MH Archives, as well as in her books. It is up to contemporay MHs not just to “answer” that question, but to recreate it as a revolutionary need of our time.