From the July-August 2016 issue of News & Letters

by Eugene Gogol

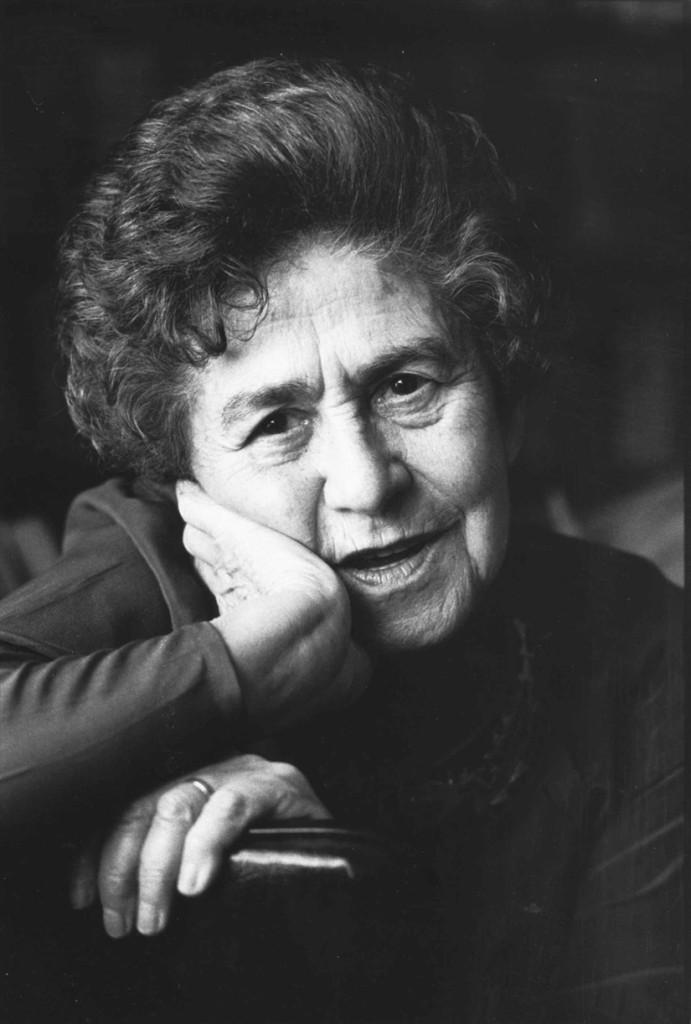

The radical heart of Hegelian dialectics is not alone negation—the No, the rejection of and refusal to accept what is our unfree reality—but the negation of the negation—the Yes, the positive within the negation, that constructs the new. Surely Marx recognized this heart of dialectical thought, appropriating and reconstructing it on revolutionary grounds, working out his thoroughgoing naturalism or humanism in his 1844 Economic-Philosophic Manuscripts. Raya Dunayevskaya, the founder of Marxist-Humanism, would term 1844 Marx’s “philosophic moment” that began his trajectory as revolutionary thinker-activist over four decades—Marx as philosopher of revolution in permanence.

Read The Philosophic Moment of Marxist-Humanism to learn more about “the philosophic moment. To order, click here.

Was there then no further need for Marxist revolutionaries to return to Hegel? Evidently Lenin, under the impact of the shocking betrayal by the established Marxism of the Second International at the outbreak of World War I, did not think so. He returned to Hegel’s Science of Logic. Dunayevskaya would designate Lenin’s Notebooks on Hegel as his “philosophic preparation” for 1917.

A further crisis within Marxism occurred with the transformation of the Russian Revolution into a state-capitalist monstrosity under Stalin, and the 1939 Hitler-Stalin non-aggression pact giving the green light to the Second World War.

This betrayal of Marxism from within, in the name of so-called Marxism, meant the need to find new beginnings for revolutionary Marxism (Marx’s Marxism). By 1953 Dunayevskaya had already analyzed Russia as state-capitalist, had found and translated Lenin’s Notebooks on Hegel, and had been reading and translating excerpts of Marx’s 1844 writings. She was compelled to once again return to the Hegelian dialectic, to Hegel’s Absolutes.

The State-Capitalist Tendency, of which Dunayevskaya was a leader along with C.L.R. James and Grace Lee, had finally left Trotskyism to form Correspondence Committees, and sought to find a basis for a Marxist organization within Hegelian dialectics. James had termed it the “Dialectic of the Party,” and Dunayevskaya accepted this term as she began her exploration of Hegel’s Absolutes.

FROM APPLYING TO RECREATING DIALECTIC

For many, Dunayevskaya’s starting point of “the dialectic of the party” is surely a red flag. I can understand such a response after the deeply contradictory history of vanguardism, the outright acts of repression and dictatorship under the vanguard party of Stalin and Stalinism for much of the 20th century. However, I would ask you to enter with me into the Hegelian dialectic of negativity, of both negation and negation of the negation, to explore Dunayevskaya’s letters and her own second negativity when she was within the Absolute Idea, Absolute Knowing and Absolute Spirit of Hegel’s dialectic.

Yes, she began with Dialectic of the Party. You can find my commentaries on that on pages 300-301 of Towards a Dialectic of Philosophy and Organization. I call these “applications” of the dialectic—applying the dialectic to the party. Below I will contrast this to what I call “recreating the dialectic.” Though Dunayevskaya used the term vanguard party, and perhaps had not fully yet broken with all aspects of the vanguard party, two aspects of her view were in opposition to the classical formation of the party. First, she was already practicing a concept of the masses as creative in their activities and as source for revolutionary theory. One can see this in her 1940s writings on the independent struggle of Black people in the U.S. Later, in 1963, Dunayevskaya would write a book on the history of Black struggle in the U.S.: American Civilization on Trial: Black Masses as Vanguard—a quite different concept of vanguard than the party.

We see her relation to workers, also non-vanguardist, in her activity with workers in the Coal Miners’ General Strike of 1949-50. So important did she view the activities of the miners in their general strike, and the participation of the state-capitalist tendency in that activity, that later she would designate this experience as one of the threads that led to “the birth of Marxist-Humanism in the United States.” Why? Because it was here that she came to see the practice of the workers as itself a form of theory. No, she did not enunciate this expression at that moment, but the seeds of this concept were born here.

THE OBJECTIVITY OF SUBJECTIVITY

Second, when she wrote of “the type of grouping like ours,” she had in mind not the orthodox Marxist parties with their programs, but what I would term a strictly theoretical-practical grouping that was searching for the philosophic basis of its existence, what she would later call ”the objectivity of subjectivity.” This is far, far away from classical vanguardism.

The key here is not alone to see her beginning point in Dialectic of the Party, but where Dunayevskaya’s explorations of Hegel’s Absolutes would take her. Her thought-dive went far deeper, transcending “the Dialectic of the Party.” It is here that we will find her breakthrough on Hegel’s Absolutes, “the Philosophic Moment of Marxist-Humanism.”

Dunayevskaya’s breakthrough meant a completely different reading than both Hegel scholars and Marxist revolutionaries had given. Hegel’s Absolutes had in general been seen as a complete idealism where humanity was shut out, perhaps a conversation with God, or simply a summary or recapitulation of what he had developed earlier, with nothing new in the sections on the Absolutes.

DUAL MOVEMENT OF PRACTICE AND THEORY

Dunayevskaya discovered something quite different. She saw within Hegel’s absolutes, not an end point, but new beginnings, Absolute Negativity as New Beginning. What did she mean by this? She saw, particularly in the final syllogisms of Absolute Mind (Spirit) at the end of Hegel’s Philosophy of Mind, a dual movement—a movement from practice to theory that she recognized was itself a form of theory, and a second movement, a movement from theory to meet this movement from practice. Furthermore, this second form of theory not alone joined with the movement from practice, but was itself rooted in, or reached back to be forged in the fullness of philosophy—that is, theory as a concretization, an expression of emancipatory, dialectic philosophy.

Let us think through what this means. First, if there is a movement of masses from below, workers, women, minorities etc. and that movement from practice is itself a form of theory, is itself not alone force or muscle, but reason, mind, of revolutionary transformation, then that realization means that the old form of the party to lead, vanguardism, was completely bankrupt. You did not need “to give consciousness to the masses,” the masses would develop that on their own in the process of struggle, in the process of negation of the old. Didn’t that mean that Dunayevskaya had, via this dialectical exploration, moved far beyond any Dialectic of the Party?

But wait, there is more. Yes, the movement from practice was a form of theory, but not the only form of theory. There was another form of theory—that which revolutionaries or radical activists could work out to join, to be in unity with, the movement from below, from practice that was implicitly theory. Note my use of the word implicit. The form of theory from the masses was not always full-blown theory, but theory was implicit. Now, there was a truly integral, dialectic role for revolutionary theoretician-activists. It was not to give consciousness to the masses, rather it was to help the masses transform what is implicit in their practice and make it explicit as the basis for revolutionary transformation. It was in that manner that “we [would enter] the new society.”

WHAT KIND OF THEORY IS NEEDED?

But how could these small groups of theoretician-activists be able to do this? If they were to meet the movement from practice that was itself a form of theory, with a concept of revolutionary theory that would truly be integral to the masses’ practice, to their form(s) of theory, then what kind of theory needed to be worked out to undertake such a task? It could only be theory that had its roots emanating from, reached back to dialectical philosophy—only theory that was a concretization of the fullness of emancipatory philosophy. That is, it needed to be profoundly related with the totality, the fullness of a philosophy of revolution—the historically created Hegelian-Marxian dialectical philosophy.

This, precisely this, is the contribution of Dunayevskaya: The dual movement, from practice that is a form of theory, of theory that makes explicit the masses’ own practice and thoughts and that can do so precisely because such theory is rooted in the fullness of philosophy. It is this, I would argue, that makes Dunayevskaya’s contribution on a different level, a different philosophic plane, than that of other thinkers. This is what I mean when I write of the need to “recreate the dialectic” rather than to “apply” that dialectic. It is not to dismiss or degrade other thinkers—Lukacs, Marcuse, Korsch and others. Yes, they have made contributions. And I am sure we would add many others. But, can we not grasp that Dunayevskaya’s contribution philosophically, and I would add even practically in terms of concept and practice of revolutionary organization, is of a different type? This is not because she was smarter or wiser than any of the others. Rather, it was because she lived in a certain age, with a deeper maturity of the movement from below. She saw and identified with this maturity and ran with it to the Absolutes of Hegel, and within those absolutes, she found the philosophic expression of that maturity that had not been explored fully even by Marxists as great as Marx or Lenin. Again, not because she was “more advanced” than they, and certainly she had never claimed that. Rather, it is because of the maturity of the post-World War II world that opened to Dunayevskaya a new vantage point, and thus a new way of reading Hegel, of reading Hegel’s absolutes as new beginnings. That is what I see is involved in her Letters of May 12 and 20, 1953.

RELATION OF ORGANIZATION TO PHILOSOPHY

One other note on the dialectic in Dunayevskaya’s exploration of Hegel’s Absolutes. Over more than three decades, she returned numerous times to those Letters, to finding what she termed “the many universals” inherent in them. In 1986-87, she turned to the letters, not to explore “the Dialectic of the Party,” but the dialectic of organization. She was asking what is the relation between organization(s) of revolutionaries and dialectical philosophy? She formulated this as: “Dialectic of Organization and Philosophy: ‘The Party’ and Forms of Organization Arising from Spontaneity.”

Thus, it is the dialectic in philosophy that allows one not only to break with the vanguard party form (a first negation if you will) but to enter onto a path of working out revolutionary organization not alone as form, but as unseparated from emancipatory philosophy as the very being, essence and notion of such revolutionary organization(s) (an entering fully into second negativity).

First published in Spanish in Praxis en America Latina, after it published Raya Dunayevskaya’s May 1953 Letters on Hegel’s Absolutes.

Special offer on:

The Power of Negativity: Selected Writings on the Dialectic in Hegel and Marx by Raya Dunayevskaya

The essays in this book, including those discussed in the “Philosophic Dialogue” above, show why serious Marxist thinkers and revolutionaries return to Hegel, the source of the radical dialectic, as Karl Marx did repeatedly.

This work contains essential discussions on Hegel, including on his Absolutes. To order, click here.

Whether the reader wants insights into Marxist thinkers—from Lenin to Frantz Fanon to those in the Frankfurt School or contemporary thinkers of the 20th and 21st Century—or of philosophy’s relevance to revolutions from the Black struggle for freedom in the U.S. to Africa, the Middle East, and the Balkans, there is an essay in The Power of Negativity that will shed an original radical light on the subject.

The special offer for The Power of Negativity includes $10 off the original price of $25 PLUS a year’s subscription to News & Letters. To receive both book and subscription send $15 to News and Letters, 228 S. Wabash Ave., #230, Chicago, IL 60604, or use PayPal from our website.