From the September-October 2016 issue of News & Letters

by Franklin Dmitryev

[E]verybody wants to get further. But there are two ways of going further—a backward and a forward. The light of criticism soon shows that many of our modern essays in philosophy are mere repetitions of the old metaphysical method….

—G.W.F. Hegel

Statue of G.W.F. Hegel

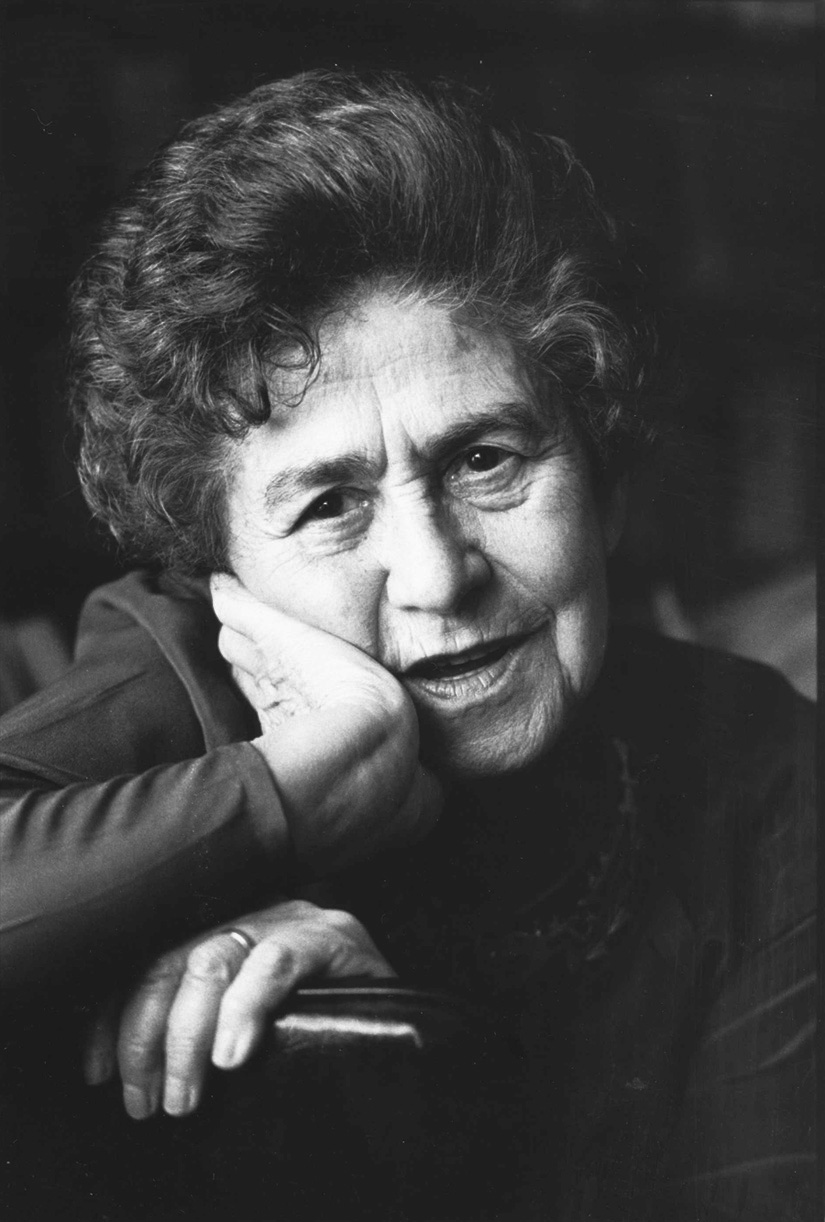

The recognition of what was new in Karl Marx’s revolutionary thought in his final decade marked a crucial point of development in Marxist-Humanism. First articulated in Raya Dunayevskaya’s book Rosa Luxemburg, Women’s Liberation, and Marx’s Philosophy of Revolution, her comprehension of these “new moments” informs her view of the needed total uprooting of this racist, sexist, capitalist society. These moments included the relationship between industrialized capitalist countries and colonized or non-capitalist societies; the dialectical concept of multilinear paths of human development that Marx discerned, vs. the unilinearism of Frederick Engels; a deepening of his concept of the needed transformation of Man/Woman relations; and the relationship between philosophy and organization.

The discoveries of Marx’s last decade resulted in a new view of Marx’s life-work and philosophy as a totality. Dunayevskaya also created an opposing category of “post-Marx Marxism as pejorative”; even the greatest Marxist revolutionaries—beginning with Engels during Marx’s lifetime—had never grasped that totality and instead developed separate aspects. Thus Dunayevskaya stressed that the category was not chronological but critical.

TURNING PHILOSOPHY INTO SOCIOLOGY

Today some former Marxist-Humanists have quietly dumped this and other central principles and retreated into the post-Marx Marxist academic milieu, while still claiming to be Marxist-Humanists. Take Kevin B. Anderson’s book Marx at the Margins: On Nationalism, Ethnicity, and Non-Western Societies (2010, University of Chicago Press). Its whole thrust is to amplify selected conclusions Dunayevskaya drew about the new moments of Marx’s last decade. Anderson performed a major work of excavation in Marx’s texts to back up those conclusions, though confined to the questions of the relationship between capitalist and non-Western societies, and on national liberation movements. These are separated from the question of organization, while women’s liberation garners only passing mention.

At the same time, Anderson turns her conclusions into sociological theory stripped of Marxist-Humanism and placed in a quite different philosophical context. Totally missing from the discussion of multilinearity is Dunayevskaya’s point that:

“Post-Marx Marxists failed to grasp this because they separated economic laws from the dialectics of revolution. For Marx, on the other hand, it was just this concept of revolution which changed everything, including economic laws….None seem to have even begun to grapple with what it meant for Marx…to have so fully integrated the dialectic and the economics as to articulate that the socialism that would follow the bourgeois form of production signified ‘the absolute movement of becoming.’”[1]

Anderson refers to Marx’s philosophy not as philosophy but as “a theory of history and society” (pp. 237, 244-45). That is consistent with his overall approach, which does not show the connection of what he takes from Marx with the totality of Marx’s body of ideas.

Anderson does not even mention revolution in permanence, although Dunayevskaya saw Marx’s writings on non-Western societies and multilinearity as a further development of that concept. Despite her stress on their relationship to the “philosophic moment” of the birth of Marx’s new Humanism in 1844, the latter is essentially absent from Marx at the Margins.

To be sure, the word “dialectic” is sprinkled in the text, but only meaning a tool in the hands of theoreticians, usually referring to taking note of contradictions. The all-important “negation of the negation” only appears in connection with one quote from Marx’s Capital (pp. 171, 226-27). Dunayevskaya’s conclusions are thus torn from the context of her overarching summation of the significance of Marx’s new moments.

The conclusion of Marx at the Margins three times reduces Marx’s philosophy to “a theory” and reduces its significance to concentrating “increasingly on intersectionality.”

It ends by calling this theory’s “direct relevance” to today “limited.” Its greatest importance, we are told, is “at a general theoretical or methodological level, however. It can serve an important heuristic purpose, as a major example of his dialectical theory of society….At the level of intersectionality of class with race, ethnicity, and nationalism….Marx’s writings on these issues can help us to critique the toxic mix of racism and prisonization in the U.S., or to analyze the Los Angeles uprising of 1992, or to understand the 2005 rebellion by immigrant youth in the Paris suburbs” (p. 245).

Never does the book confront the question, always central to Marxist-Humanism: what happens after the revolution, to prevent its transformation into opposite and continue it to the establishment of totally new human relations. Marx at the Margins omits what Dunayevskaya called

“the most fundamental division of all, the one which characterized all class societies…is the division between mental and manual labor. This is the red thread that runs through all of Marx’s work from 1841 to 1883. This is what Marx said must be torn up root and branch. But of that Great Divide, so critical to our age, there is not a whiff in [Hal] Draper.”[2]

RETREAT INTO POST-MARX MARXISM

The meaning of “post-Marx Marxism as pejorative” is turned into its opposite by Anderson, who only uses it chronologically, as does his colleague Peter Hudis in Marx’s Concept of the Alternative to Capitalism (2012, Brill).[3]

It is not just that Hudis and Anderson strip the phrase of Dunayevskaya’s meaning; this was inevitable precisely because they have rejected the category.

Both books quote Dunayevskaya a few times and Anderson credits her as “my intellectual mentor” (Marx at the Margins, p. viii), although they fail to acknowledge that most of their conclusions are taken from her. Anderson notably omits mention of her in places where she should clearly be cited, e.g., when he names writers who critique Engels on the dialectic along the same lines he does (p. 5). And he lumps her take on Marx’s writings on slavery and the Civil War in with those of Eugene Genovese[4] and bids the reader to keep “in mind these varying interpretations” (p. 83).

All this reflects something deeper. Anderson and Hudis are at home in post-Marx Marxism—which today has turned Marx’s revolutionary vision into an academic field of study. Again and again they assimilate themselves, Marxist-Humanism and Dunayevskaya into the Marxist crowd, as “one among many,” as if the very meaning of “post-Marx Marxism as pejorative” were not to make a sharp division between Marx’s philosophy and “Marxism.”

ORGANIZATION AND PHILOSOPHY

Dunayevskaya grasped Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Program as containing a concept of revolutionary organization whose ground is the philosophy of revolution in permanence. Its perspective must be for the revolutionary transformation to be total from the start, continuing from the day after the conquest of power until

“a new generation can finally see all its potentiality put an end once and for all to the division between mental and manual labor.”[5]

That view of the Critique was the basis of Dunayevskaya’s work on dialectics of organization and philosophy, unfinished at her death. Her organization, News and Letters Committees, adopted the task of continuing the work. When Hudis and others gave up on this exceedingly difficult task, they substituted for it the plan to “work out an alternative to capitalism.”

The one original thought to emerge from this project was Andrew Kliman’s reading of the Critique as entailing a concept of “equal remuneration,” that is, every hour of labor was to be rewarded equally:

“Yet I think that there is an important sense in which [Marx] theorized this emergence [of the new society] as an absolute liberation rather than as a transition. I refer to his notion that people will be remunerated in accordance with the amount of work they do, from the very start….So one of the most fundamental tasks we face today, I believe, is to work out how to create the social conditions such that each hour of labor will really count as equal—beginning on the day after the revolution.”[6]

Hudis seized on this original deviation. It is the key point of his book, though he stopped crediting Kliman after breaking with him in 2009 and now phrases it as “Marx’s all-important concept of remuneration based on labor-time” (p. 195n40).

While the Critique of the Gotha Program plays no part in Marx at the Margins, it is the topic of one of the longest sections of Hudis’s Marx’s Concept of the Alternative. However, just as absent is the Critique’s supreme significance to Dunayevskaya—as Marx’s new moment on organization—and her point that post-Marx Marxists had “separated Marx’s concept of revolution from his concept of organization.”

Hudis has nothing to say about organization except to repeat several times the well-known fact that Marx did not endorse a party ruling over the proletariat.

The whole book approaches its title mission, to seek Marx’s Concept of the Alternative to Capitalism, within a narrow economistic framework.[7]

The Critique is read almost entirely as a treatise on the need for the new society to distribute consumption goods, initially, according to one’s individual time of labor.

This narrow interpretation leaves labor at the level of a quantifiable object. Hudis mentions free labor vs. alienated abstract labor, but what is really concrete in his eyes is that the measure of postcapitalist society “lies in the distinction between actual labour-time and socially-necessary labour-time” (pp. 159-60; see also pp. 190-91, 193-94, 203). He should have remembered Dunayevskaya’s point that the absolute opposite of the socially necessary labor time of value production is not equal pay for equal labor time but time as “the space for human development.”

DOWN THE RABBIT HOLE

Instead he clings to the one original contribution made by Kliman: making every hour of labor equal. How can the homogenizing of concrete labor be part of a Marxian vision of the new society? The specific character of labor in capitalist production has to do with pounding all concrete labors into one homogeneous mass—and thus labor assumes a thingified form.

The Kliman-Hudis thesis is based on an interpretation of the Critique of the Gotha Program that contrasts sharply with that of Dunayevskaya, who wrote:

“Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Program is the finest critique in the sense of seeing that the revolution in permanence has to continue after the overthrow….So the point is the recognition of what Marx meant by revolution in permanence, that it has to continue afterwards…and the fact that you have to be very conscious that until we end the division between mental and manual labor…we will not really have a new man, a new woman, a new child, a new society.”[8]

Hudis allows that Marx “does not intend for his critique to be read as a detailed blueprint,” but then assumes that Marx is actually “spelling out an alternative” centering on distribution by labor time.[9]

In reality Marx was demonstrating the need for revolution in permanence, by spelling out an immanent critique of the Gotha Program’s loose Lassallean conceptions of “equal right,” “fair distribution,” and “undiminished proceeds of labor.” He showed how “equal remuneration” turns into its opposite because of the inherent defects of “bourgeois right.”[10]

To obscure the undue stress on distribution, Hudis switched to the phrasing “directly social vs. indirectly social labor.” Rather than developing Marx’s concept of directly social labor, however, he reduced it to another name for equal distribution.

DIRECTLY SOCIAL LABOR: HUDIS vs. MARX

Hudis writes as if directly social labor is to be introduced in the new society. Marx pointed to directly social labor already operating in capitalism through cooperation in the process of production.[11] Dunayevskaya saw this as a new mass power that needs to be released from the value-form to develop freely.[12] She relates this collective power of masses to the experience of the Paris Commune and freely associated labor, which is Marx’s most precise development of what would liberate directly social labor from its capitalist integument. Freely associated labor was central to Dunayevskaya, but Hudis makes it secondary to “directly social labor” as the key to the new society (pp. 157-60, 191, 194, 197).

Hudis and Kliman had justified their project based on the claim that the masses would not move until they were presented with a “viable alternative to capitalism.” They had retreated to the standard post-Marx Marxist attitude that the masses are backward. And yet the founder of Marxist-Humanism, Raya Dunayevskaya, always singled out as her philosophic breakthrough her discerning of the movement from practice that is itself a form of theory.

Hudis and Kliman had justified their project based on the claim that the masses would not move until they were presented with a “viable alternative to capitalism.” They had retreated to the standard post-Marx Marxist attitude that the masses are backward. And yet the founder of Marxist-Humanism, Raya Dunayevskaya, always singled out as her philosophic breakthrough her discerning of the movement from practice that is itself a form of theory.

But Hudis now openly rejects Dunayevskaya’s foundational category. He writes:

“Marx does not equate the consciousness that emerges from the oppressed with revolutionary theory. The latter does not emerge spontaneously from the masses, but from hard conceptual labor on the part of theoreticians” (p. 80).[13]

This is the self-written obituary of the former Marxist-Humanists, who built their academic careers on cannibalizing Dunayevskaya’s conclusions while quietly dismantling their philosophical framework.

[1] Raya Dunayevskaya, The Power of Negativity: Selected Writings on the Dialectic in Hegel and Marx (2002, Lexington Books), pp. 259-60.

[2] Raya Dunayevskaya, Rosa Luxemburg, Women’s Liberation, and the Dialectics of Revolution, p. 105. The reference is to Draper’s Karl Marx’s Theory of Revolution, of which Dunayevskaya remarked, “Draper is good only at ‘excavation,’ and remains confined within his own narrow Trotskyist framework when it comes to analysis” (p. 163n16).

[3] See Hudis, pp. 89n227, 152; Anderson, p. 57. Hudis is leader of the cluelessly named IMHO, or International Marxist-Humanist Organization.

[4] Anderson does not mention that, at the time of writing what he cites, Genovese was a defender of “Comrade Stalin, who remains dear to some of us for the genuine accomplishments that accompanied his crimes” and later moved to the neo-Confederate Right.

[5] The Power of Negativity, p. 5.

[6] Andrew Kliman, “Alternatives to Capitalism: What Happens After the Revolution?” Sept. 5, 2004, http://static1.1.sqspcdn.com/static/f/25940/124100/1118693289267/Alternatives+to+Capitalism.doc. Like Hudis and Anderson, Kliman quit News and Letters Committees in 2008 but still calls himself a Marxist-Humanist.

[7] For instance, in 22 pages on Capital, Volume I, Hudis does not mention how it takes up the potential in postcapitalist society for “a higher form of the family and of the relation between the sexes,” as Dunayevskaya put it in Women’s Liberation and the Dialectics of Revolution: Reaching for the Future (1996, Wayne State University Press), pp. 197-98.

[8] Women’s Liberation and the Dialectics of Revolution, p. 181.

[9] So dogmatically does Hudis insist on “the necessity of remunerating individuals based on actual labour-time….Nor is it possible to leave behind such cardinal principles of the old society as basing remuneration on an exchange of labour-time for means of consumption” (pp. 203, 209) that even where Capital projected that the mode of distribution of postcapitalist society “will vary….We shall assume [distribution by labor time], but only for the sake of a parallel with the production of commodities” (emphasis added), Hudis reads it as a statement that the new society must do so (pp. 157, 198).

[10] This argument is detailed in my “Reading Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Program,” in Pre-Convention Discussion Bulletin #2, August 2006, News and Letters Committees.

[11] A detailed examination can be found in my “Marx on directly social labor,” in Interim Discussion Bulletin #1, January 2006, News and Letters Committees.

[12] See her Marxism and Freedom, from 1776 until Today, Chapter 6.

[13] Marx at the Margins does not mention the movement from practice as a form of theory.

Read Raya Dunayevskaya’s Marxist-Humanist trilogy of revolution for yourself

Marxism and Freedom dialectically presents history and theory as emanating from the movement from practice, re-establishing the American and world humanist roots of Marxism.

“Cooperation is in itself a productive power, the power of social labor. Under capitalistic control, this cooperative labor is not allowed to develop freely. Its function is confined to the production of value. It cannot release its new, social, human energies so long as the old mode of production continues.”

Philosophy and Revolution shows the integrality of philosophy and revolution as characteristic of the age, tracing it through historically, and shows that Marx’s philosophy of liberation merges the dialectics of elemental revolt and its Reason.

“The days are long since past when these voices from below could be treated, at best, as mere sources of theory. The movement from practice which is itself a form of theory demands a totally new relationship of theory to practice.”

Rosa Luxemburg, Women’s Liberation, and Marx’s Philosophy of Revolution discovered a trail to the 1980s in Marx’s “new moments” on new paths to revolution, on new concepts of man/woman relations, and on philosophy of revolution as inseparable from organization.

“What became as translucent, when out of the archives had come Marx’s unpublished draft letters to Vera Zasulich, was Marx’s concept of permanent revolution. This made clear, at one and the same time, how very deep must be the uprooting of class society and how broad the view of the forces of revolution.”

Anderson, Hudis, and Kliman have forgotten the history of Marxist-Humanism, a body of ideas which has deep roots in the 1949-50 West Virginia Coal Miners’ strike. That action by workers was in fact a breakthrough in theory. The miners didn’t ask how they should be paid or how the products of labor should be distributed or consumed, but asked instead “What kind of labor should we be doing?” That moment helped lead to the emergence of Marxist-Humanism as a distinct philosophy. These pretenders have not escaped the fetish of the commodity and have fallen back to decades before the mid-20th century in their thinking. In fact, however they may characterize themselves, they have unwittingly abandoned Marxism altogether for a flood of abstractions that lead to ‘Nowheres-ville.’

Not to reduce Marx’s philosophy of revolution into “a theory” –or, in other words, not to separate “social critique” from the absolute subjective-objective mass movement of becoming–, but to keep them as a unity, is the major challenge that thinker-activists and social movements face today. “Epigones discard Marxist-Humanist philosophy” gives us a wake-up call about this. Along with the unity of theory and practice comes the question of organization, which is the “third term” in this dialectical view. But, when one gives up “on this exceedingly difficult task,” as the authors criticized in the essay seemed to do, the only option remaining for theoreticians is their own plans “to work out an alternative to capitalism.”

The essay, then, speaks to our present moment, when a large number of “revolutionaries” still see Marx’s Marxism as “one among many,” as if the very meaning of “’post-Marx Marxism as pejorative’ were not to make a sharp division between Marx’s philosophy and ‘Marxism.’”

Thus, the quote that opens the essay could not be more appropriate: “[E]verybody wants to get further. But there are two ways of going further—a backward and a forward. The light of criticism soon shows that many of our modern essays in philosophy are mere repetitions of the old metaphysical method.”